Neil Gaiman’s writing often features the allegedly radical free sexuality of temple prostitutes in ancient Greece and Babylon. I wonder if Gaiman’s underlying ideology is the third rail of shock electrifying recent exposes regarding his character. For those unaware, “five women have now made allegations of sexual assault and abuse against Gaiman, with the timeline of his alleged misconduct going back to 1986.” Of course his behavior has directly affected productions of Sandman on Netflix and Good Omens on Amazon Prime. Though perpetrators of sexual violence have often appealed to the trope of temple prostitutes as justification for this brand of evil, one ready example in pop culture comes from Neil Gaiman’s SANDMAN. In the seventh volume entitled BRIEF LIVES, a love goddess Ishtar once worshipped by temple prostitutes finds herself reduced to selling her body at a strip club in 1980’s America. Her stripper colleague Nancy rhapsodizes about temple prostitution to her and another stripper named Tiffany:

“I [studied temple prostitution] in college. The near-east, right? Two, three thousand years ago, one of the love goddesses. Astarte, maybe. Every woman in that country had to go to the temple, once in her life. All the women waited in the temple courtyard. Each one had to wait there until a stranger offered her a coin. Whoever he was, she had to go with him, and they’d make out. I think there were rooms in the temple to do it in. …I remember that it didn’t do anything to your virginity. As far as the world was concerned if you lost your cherry in the goddess’s courtyard, you still kept your cherry. Was that what you were thinking of, Ishtar?”

“Yes,” Ishtar says. “The temple courtyard and the women waiting. Once in each of their lives. It was the most significant of all the rituals — a terrifying experience for both the women and the men, where they gave themselves to lust and the unknown.”

Nancy says, “One of our professors said that sacred prostitution is something that only evolves in matriarchies — men are so terrified of female sexuality that they have to repress it, or regulate it — which is where we come in.”

Though I could deconstruct several fallacies therein (such as who in their right mind would call Babylon, Greece, or Rome matriarchies? or when is losing keeping? etc.), let us focus specifically on this idea that the ancients thought nothing malicious — nothing nefarious — went on at a temple with prostitutes. Is it any surprise that in 2007, Gaiman expressed great personal interest in writing a film adaptation of The Epic of Gilgamesh? [Ambrose, Tom (December 2007). "He Is Legend". Empire. p. 142.]

Surely said ancient texts themselves would support such a position, right?

The debate on this bled over into translations of Gilgamesh, for instance. The word “harimtu.” Some translate the word as “temple prostitute” or “sacred prostitute” and others as “harlot” or “whore” or whatever slut shaming word suited the translator at the time. All of that aside, I find it fascinating that a harem is both a word we use for the very orgy romance novels that try to imitate this culture as well as a word for the private part of the home of a polygamous person in this era. It comes from the word haram meaning sin, the word my Arab friends still use today, which comes from the word for temple, the sort of place you might find a harimtu. It’s one of these words that has a cognate in every part of speech: subject, object, verb, etc. I, frankly, don’t care about translation choice in this instance because literal meaning is generally found in paragraphs — through historical and literary context coupled with virtuous allegory — as opposed to a single word study. (That’s to say nothing for allegorical, analogical, moral, and other meanings of various texts, but none of these as such lie within the purview of this essay).

Other authors, however, do care very much about the word chosen in translation because some believe the former words like “temple prostitute” do not convey the negativity of the latter words like “harem romance” and “hooker.” I find it absurd to believe temple prostitution conveys none of the negativity of modern prostitution and therefore was a good. That logical syntax alone is silly: a society can have a bad that is a different sort of bad compared to the original model and still be bad. The existence of avarice doesn’t negate the existence of wrath, in fact they often compound as we see in the military industrial complex as *checks notes* even John the Baptist warned. That aside, if the idea’s roots are good, modern prostitution always practices that same good, right?

But if modern prostitution is always good, why make the distinction in the first place?

What’s wrong enough that something needs defending or explaining or justifying at all? Isn’t goodness its own reward and defense?

From Gilgamesh, the frequent argument goes that both Enkidu and the prostitute of Ishtar did no wrong. The passage seems to imply that sex civilized him. Many modern arguments follow that she and he, therefore, were not only justified but holy in the act. This argument has been used by perpetrators before.

Yet as with all translation and interpretation, meaning comes in pericopes. In the context of Gilgamesh, we discover the reason people cry to the gods to provide Enkidu as challenger to Gilgamesh:

“Gilgamesh’s lust leaves no virgin to her lover, neither the warrior’s daughter nor the wife of the noble.”

From the small of them to the great, they’re jealous and angry about Gilgamesh’s adultery — or perhaps something even more nefarious in the perpetrator. Once Enkidu is trained up by the prostitute, a man approaches him and says:

“Gilgamesh has gone into the marriage-house and shut out the people…. Gilgamesh is about to celebrate marriage with the Queen of Love and he still demands to be first with the bride, the king to be first and the husband to follow, for that was ordained by the gods from his birth. But now the drums roll for the choice of the bride and the city groans.”

They’re angry because, fundamentally, this is wrong. Set aside for a moment the utter lack of historical evidence for droit du seigneur extending beyond primitive societies into Medieval Europe (see Britannica and others), George R.R. Martin’s use of “king-first” bridal beds also seems to miss this nuance even in the example of primitive societies: the husband and wife ought to enjoy one another alone and Gilgamesh ought not interfere. That “ought” speaks volumes. So they send Enkidu to fight Gilgamesh and Enkidu stops him right at the doorframe of the bridal bed. A massive fight ensues. Enkidu wins.

Later, Ishtar herself — she of the temple for whom there are said prostitutes, she who becomes a prostitute and strip club dancer in Neil Gaiman’s version — proposes that Gilgamesh marry her. He refuses to make her his wife because “lovers have found you like a brazier which smolders in the cold” — a rather unintended hilarious pun in both English and French — “a backdoor which keeps out neither squall of wind nor storm, a castle which crushes the garrison,” — I won’t make anatomy commentary here — “pitch that blackens the bearer, a water-skin that chafes the carrier, a stone which falls from the parapet, a battering-ram turned back from the enemy,” — one truly begins to wonder how far the euphemism can be stretched — “a sandal that trips the wearer. Which of your lovers did you ever love forever?”

He goes on to specifically, carefully outline all of her unfaithfulness. I find this all rather hypocritical considering Gilgamesh’s previous exploits, considering how his society favors him, considering how there’s absolutely no way this benefits the woman in the prostitution circle proportionately. Humans haven’t changed in our hypocrisy.

Enkidu then literally calls the fare she’s offering him “tainted and rotten.”

Because of later foul play, Enkidu goes on to shower a litany of curses upon the harimtu, appealing to what seems to be the direct experience of the downsides to her trade. “You shall be without a roof for your commerce,” which is literally true, and “do your business in places fouled by the vomit of the drunkard,” which is almost obviously true if modern observations and ancient texts about the sort of men who hire prostitutes bears out. Enkidu reveals the truth, “For I too once in the wilderness with my wife had all the treasure I wished.”

The gods get angry at him for cursing the harimtu and he changes his mind to bless her. But even his blessing ends in a curse:

“On your account a wife, a mother of seven, was forsaken.”

Enkidu was not only married. He had fathered seven children. A family was destroyed for the lust between this man and this prostitute, very likely a woman caught in a kind of economic slavery and — if we agree with the demographic assumptions made by the perpetrators who wield these texts — also likely a young woman or even a girl.

But surely that’s isolated to Babylon? Surely it didn’t extend to other ancient societies?

No.

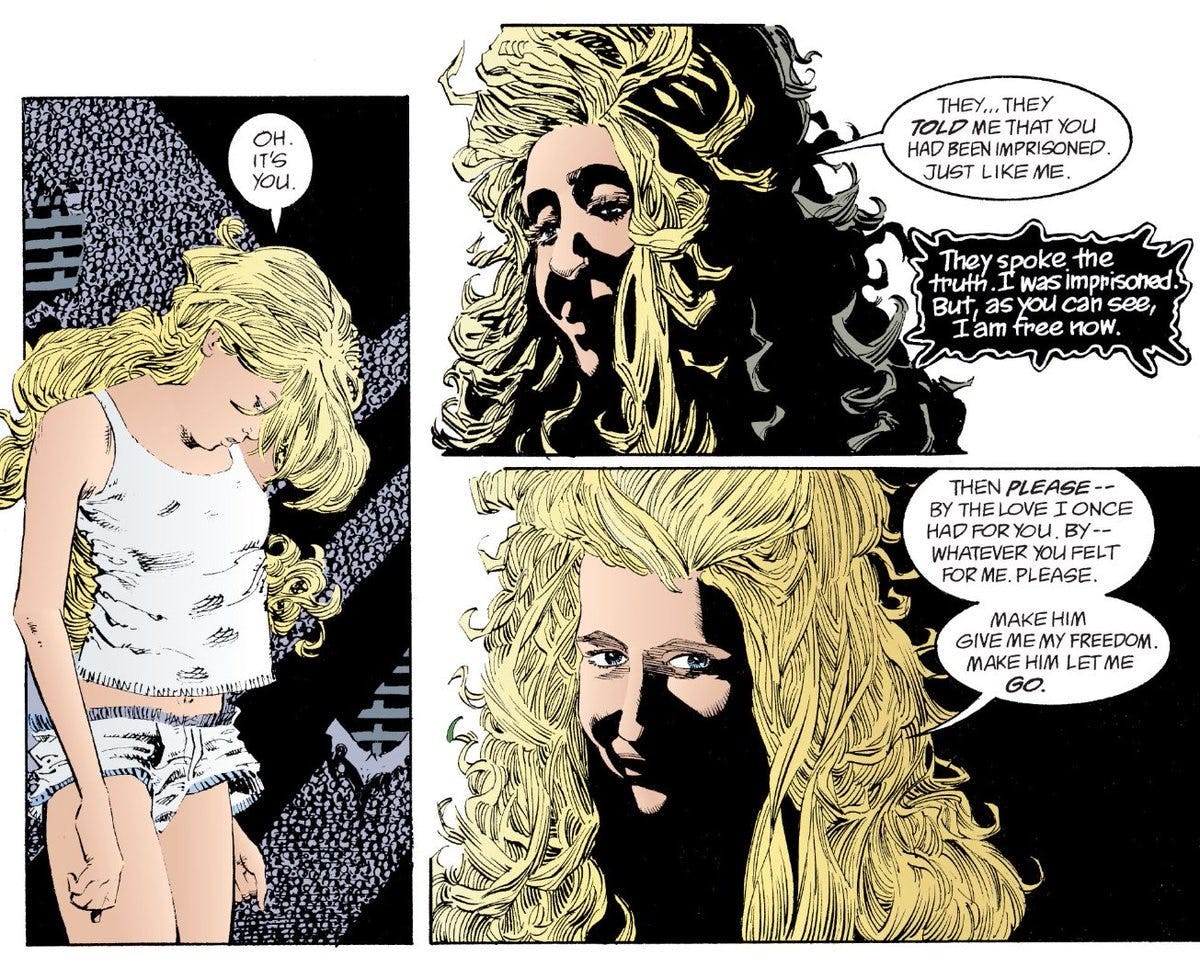

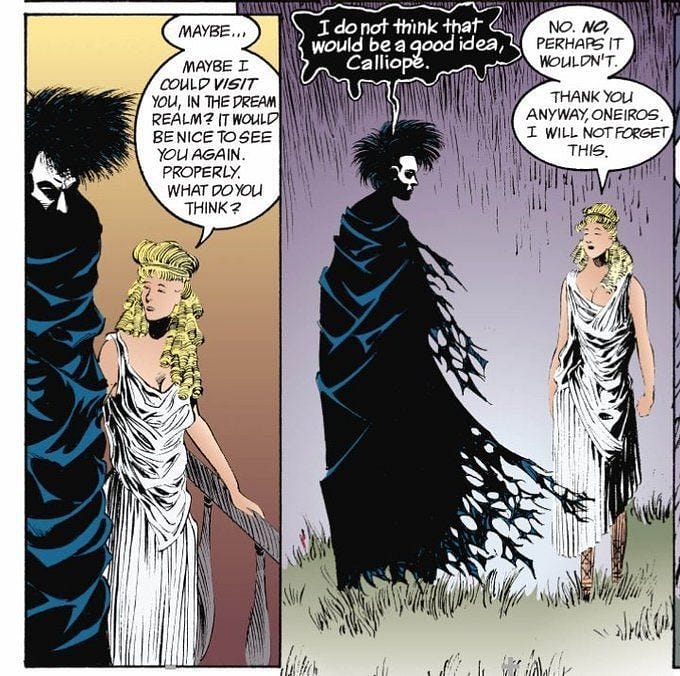

In Ovid we frequently find Juno (goddess of motherhood and children) jealous of virgins like Diana (of a similar temple to Ishtar). The entire story of Callisto — the favorite nymph of Diana’s cult — is a virgin whom Jove spies and says, “This turn is one my wife won’t learn about! But even if she were to hear of it, this prize, in truth, is worth a fit or two of Juno’s anger!” Jove then disguises himself as Diana and rapes the poor girl. Consider the very issue of SANDMAN where a young girl — a muse, allegedly — is literally raped for an author to have enough inspiration to become rich and famous for his work.

Mercy.

Sorry, I just want to take a moment. Ovid brushes over this act so many times in his book, but these things are very personal for me, my bride, many others.

Okay, when you’re ready to carry on:

When the nymphs later bathe naked, Juno sees Callisto’s belly and says:

“As if I had not had enough, this, too, was needed: you, adulteress, bore this fruit — a son.”

Certainly harsh for the poor girl. Harsher than Deianeira’s grace in Sophocles’s Trachiniae who said of her own husband:

“Hath not Heracles wedded others erenow — ay, more than living man — and no one of them hath had harsh word or taunt from me; nor shall this girl, though her whole being should be absorbed in her passion: because her beauty hath wrecked her life, and she, hapless one, all innocent, hath brought her fatherland to ruin and bondage.”

But the question is why?

Why even compare their relative harshness or mercy? In Sophocles, if it’s truly no problem for the bride or the girl or her fatherland or Heracles’s reputation, why would Deianeira — whose name means “man destroyer” — even mention it as if there’s something to forgive or overlook? In Ovid, if it’s truly a sacrifice to Diana and they’re truly still virgins, as Gaiman and his teachers assert, why would a wife — whether Enkidu’s or the wives Gilgamesh references whose husbands left them for Ishtar or Juno herself — have any claim to anger over this?

Because there is something to forgive.

There is something to overlook.

Cheating is cheating. Adultery is still adultery. In what cultures? In the cultures of these texts and every other:

‘Has he approached his neighbour’s wife?’ (Babylonian. List of Sins. ERE v. 446)

‘You shall not commit adultery.’ (Ancient Jewish. Exodus 20:14)

‘I saw in Nastrond (= Hell)... beguilers of others’ wives.’ (Old Norse. Volospá 38, 39).

I won’t cite every ancient text in every ancient culture, but we just spanned five continents in three quotes. The list goes on, those who know the texts know. Those who don’t, well…

Consider how we all get angry when the person we’ve committed ourselves to — whom we love with our whole heart and life — sleeps with someone else. We use the word “betrayal.” It comes from sacrificing long term, eternal pleasures on the altar of proximate, passing pleasures. Proximate goods and ultimate goods. Real life for a false dream. And the dream becomes a nightmare.

Want to know the wildest part about all of this very obvious context?

Even Gaiman admits this in his own temple prostitute passage.

In SANDMAN, a man Matthew has been turned into a raven that accompanies the Sandman throughout the dreamworld and waking world. And when Sandman enters the strip club to talk to Ishtar (the ancient-goddess-turned-1980’s hooker), Matthew (the former man now raven) says, “Hey, I haven’t been in a place like this since I had hands. I used to love these places. I mean, my wife didn’t mind.”

“Matthew?” Sandman asks.

“Okay,” the former man says. “Maybe she’d’ve minded if she knew.”

So even in Gaiman’s mind and others like him, this fantasy world where no consequences exist for temple prostitutes and those who seek such escorts does not itself exist. It didn’t even exist for Sam Seaborn in the first few episodes of The West Wing. In fact, in a piece “I Regret Being a Slut,” the author (with whom I disagree on a great many other things and so will not link and therefore help platform here) referred to The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century, and was moved to tears by the dedication: “For the women who learned it the hard way.”

She says from her own perspective in that piece:

It’s a tough needle to thread. I’m grateful for the ability to control my reproductive cycle and make my own money. But that freedom has come at a price. The dark side of the sexual revolution is that even though it liberated women—unyoking sex from consequences has primarily benefited men.

Yes, this fantasy world where no consequences exist does not itself exist. And when we believe the lie, it benefits men like Gaiman.

For this reason, George MacDonald said that fantasy writers may invent new physical laws but in moral law they must not invent: calling a good an evil in a fantasy world will not hold water in the reader’s mind. They revolt, even if it takes decades.

But surely his flawed thinking only infects Sandman, right?

Actually most of Gaiman’s books contain groomers or grooming of some kind. Or at very least the archetype that, with a little squinting, looks identical.

Consider Coraline. Is it another dream? Or is it some online space only accessible by kids?

It’s unclear. What is clear is that Coraline’s real-world parents ignore her, barely see her when she gets poison oak, barely notice when she falls down a frigging well. Her other mother love bombs her, showering attention and gifts and praise. Coraline’s overwhelmed with presents. The love is contractual. And when her parents go missing, she doesn’t call the police. She goes to bed. Why? Because she carries the shame of the events: she thinks it’s her fault. Everything can be perfect if she will just sew buttons on her eyes. Love shouldn’t be contractual — there’s a qualitative difference between the economic proposition “after everything I’ve done for you” and a mutual vow between two adults.

Or consider Silas from The Graveyard Book, an extremely dangerous vampire who lives forever and creates a sort of emotional dependency upon the boy Bod who is now raised by ghosts.

Or Shadow Crow from American Gods, a convict whose dead cheating wife follows him around the whole story. He has a young college hitchhiker who offers him respect, deference, and collaboration allegedly because of her American spirit. But she’s a young girl that absolutely should not be save-dating some convict whose undead wife stalks him.

Or Richard Mayhew from Neverwhere, who rescues a young street girl that comes to him bleeding and weakened while he walks to dinner with his fiancee and boss. There’s even a “morning after” with this rescued girl who asks for further help from Mayhew to escape two vampires. And he’s with her in a romantic-adventure sort of way the whole story.

Or Tristan Thorn from Stardust, who abandons his courtship of Victoria Foster and falls in love with a young Yvaine, a fallen star and faerie girl. Perhaps even a manic pixie dream girl. She marries Tristan despite their inability to have children.

Or the unnamed male narrator in The Ocean at the End of the Lane, who revisits his childhood home without a memory of why and is saved by his neighbor, a young girl named Lettie, who remains with him throughout.

Or potentially even the fae love scene in the Doctor Who episode The Doctor’s Wife of the young incorporated Idris — the soul of TARDIS — whom the Doctor loves and falls in love with, though she’s been stuck in a literal box this whole time.

In any case, whether you see the grooming or not coupled with his online behavior, what is clear and consistent in almost all of these stories is a family was destroyed through a kind of forbidden romance between an older (or ancient) man and either a girl or a childish young woman who needs to grow up fast, psychologically and emotionally.

As in the ancient world, so in the modern world: families and lives are still destroyed whether by rape or by objectification of fellow humans (often by the pimp and the player, whether via gigolo or hooker), or by cheating. There is, on the policy level, a massive difference in criminalizing prostitution when compared to criminalizing pimping and hiring prostitutes. We shouldn’t punish little girls or little boys caught in slavery, for instance, but their perpetrators.

That said, there are, fundamentally, never merely two people affected by any given sex act. I contain multitudes. The affair between my namesake Lancelot and Guinevere had Camelot at stake — it’s one of the reasons I seek the Merlin timeline, I seek to tell the story backwards. I vowed myself to Tara. Vowed. I made a future appointment with myself saying this is the kind of person I want to be when I’m eighty. There were witnesses. Hundreds of them. More have gathered over the years, strengthening our vow further: do you realize how many people I respect that would haze me with a four by four if I didn’t stay faithful to her? That’s the point of a wedding and it’s one of the reasons our world’s religious still call it a moment of divine sacramentality: more than the interpenetration of one another, the divine interpenetrates the “dearly beloved gathered here today” so that we all bear direct sun-in-the-eyes witness to The Presence. Which presence? The same presence sought through some proximate good at the temple of Ishtar, some tertiary fulfillment that won’t fulfill the deeper desire, by some rake of a man who, rather than seeking the true source of the light, uses corrupted means and ends from some temple’s prostitute to reflect it through a mirror darkly. A vow affects more than Tara and I, positively, when kept. It’s why folks often ask couples upon their sixty year anniversary, “What’s your secret?” That’s the point of vowing before witnesses. That’s why people cry at weddings. On the other hand, a visit to the temple prostitute after our marriage would have also affected more than she and I, negatively. That’s, again, the point of witnesses. That’s why divorce knocks the wind out of the children of divorce. In poker, they call a vow like that pot committed: you literally go all in with one another. So why don’t we make more of them? We do sillier things every day. Consider eating. Really consider it for a moment. Why not vow?

Because it’s not the vow we fear. We fear ourselves. We fear our weakness.

We fear we do not have the chips to win the pot, the stamina to see it through, come what may. It’s not unlike the folks who refuse to vote in democracy: refusing to vote in democracy is part of the system meant to cede power to whatever nihilistic forces win. Similarly, folks who refuse to vow in love are part of the system: they too cede power to whatever nihilistic forces seek to abuse the proximate goods of the vow. Temporary quickies, money, and power are only some of those proximate goods.

At the bottom of it, we are left yet again with the fundamental problem of the modern age: we care so often about freedom to do something that we seldom consider whether we have freedom from something. Aristotle Papanikolaou in his From Sophia to Personhood says:

When I say that person is identified with freedom, I do not mean the freedom for unlimited choice, but an existential freedom from necessity. Nature is, thus, identified with a kind of necessity that personhood ecstatically overcomes and transcends.

He cites Lossky:

The idea of person implies freedom vis-a-vis the nature. The person is free from its nature, is not determined by it.

It isn’t fate to behave the way Neil Gaiman seems to have behaved, you see.

You can be free from your basest needs for the sake of your higher needs.

Yes, you are free to sleep with a prostitute under certain conditions in America (certain rural counties in Nevada, apparently). But that will never grant you freedom from a rightly jealous wife whether in Ancient Babylon or Babylon, New York. Or an angry fandom for that matter. And it will also never, even in the wildly ideal scenario that people like Gaiman imagine as something more than the barest exception, offer freedom from objectifying one another, whether in the body sold or from the body buying. No matter what goods or power are exchanged. And make no mistake the buying of human bodies, even if only for a time or only in part, is always a kind of slavery: it is slavery to offer money or fame or power to make for a moment or forever even the smallest part of another person into your property. Folks have always sold themselves into slavery, but that’s another conversation for another day (whether harm to the self is in the same category as harm to another). The higher question today is this: do you want to be the kind of human being or even follow the example of the kind of human being who, at any point or in any way, whether for an exchange of money or power or fame, owns slaves? Who in his most famous works promotes the owning of slaves by twisting the meaning of ancient sources?

It takes respect for another’s mind and self-control to be set free from objectifying one another, set free from the question of “what can I get away with?” To ask instead the question “set free from my basest deterministic necessities, how now shall I then live?”

The easiest and most common form comes with a ring and a vow to forsake all others in front of said others. Amy in the film version of Little Women insisted marriage is an economic proposition. But then again, so are all sex acts considered in their basest form: prostitution is an economic proposition as much as every claim ever filed in an HR office, the transactions that happen on Tinder, or the economic propositions (implied or explicit) offered to each of the poor women Neil Gaiman seems to have abused. Certainly none of them are prostitutes, that’s not what I’m saying, nor is the title of this piece implying that any of these women are prostitutes. Rather the title refers to his use of prostitution passages to justify terrible behavior where he has used money or power to subjugate women: his literary prostitutes who form the mouthpiece of his soapbox of abuse. (If name calling or slut shaming his victims was the intention of anyone else reading this, as I said earlier, policy should make sure that it’s the pimps, purveyors, and patrons who should be prosecuted, not prostitutes). But there is at very least a radical power dynamic at work in his relationships, disproportionately skewed towards those who have “primarily benefitted” from “unyoking sex from consequences” according to the unnamed author of that piece above. What’s going on in these situations that must be seen as an economic proposition. One of the basest sort.

The difference is that marriage is not merely an economic proposition, not even merely a kind of protection, whereas others certainly offer no more than that. If that. A rightly ordered and faithful marriage properly orders economy — on an equal exchange and equal footing between lovers and between generations — under the real value of beauty, goodness, and truth. And no, we’re not going to judge the ideal by practical failures. We’re talking about ideas: your body is more than a marketable product at some temple, friends. In fact, the sex act is itself a sort of vow — a sort of initial promise of faithfulness. Some have even called it the crux of the vow, the embodiment of it every time it happens, and therefore a betrayal when broken. The romance novel community literally has an acronym for this: HEA. Aiming at this Happily Ever After mingling of souls, some dare to even call the body itself a kind of temple.

That would make sexual abuse a kind of blasphemy, a desecration, of the temple of sex. But you won’t hear that amid the self-righteous self-justification of men who frequent the temple of Diana or Ishtar.

And certainly you won’t find it in any prooftexting eisegesis of said ancient myths by modern men who look to those self-righteous temple patrons like dirty old Gilgamesh as their guiding lights.

What you’ll find is exactly what those men and women in the strip club find at the end of that particular issue of Sandman: a demon who ensnares you by proximate desires and blows your whole building up, killing everyone inside, women and men alike, and torches all your cash. At least Gaiman’s subconscious never lied to us about his real motives and their real consequences.

In his dreams.

If you have a substack, please take a few seconds to recommend mine:

Head to your Substack's Settings page and click Details in the left navigation bar. Next to "Recommend other Substacks," select "Start recommending."

On the Manage Recommendations page, you can:

Add recommendations like Lancelot of Little Egypt

Write a blurb explaining why you recommend Lancelot of Little Egypt

Manage settings such as whether to display Lancelot of Little Egypt on your publication's homepage or include it in recommendation digests. Please consider doing both — your recommendation will help this community grow exponentially.

This was nice. Thank you for writing it.

During the rash of weddings I attended in my twenties, only one was Episcopalian, and they made the community contribution explicit. We, as the audience, were exhorted to promise to keep that couple together. I don't know if that's a regular feature of that faith or not, but it did stick out in my mind.

Our own wedding was deliberately low-key, bourbon and barbecue at a beach-house rental on Galveston Island. Neither of our families was invited; none of the vacationing guests knew the wedding was happening until they had already arrived on the island. Dress code was Hawaiian shirts. Our child was Best Baby, perched on my arm. We did have a preacher, because we couldn't find a judge to come out. He promised not to mention his God during the ceremony (a promise he broke).

I mention this because community can be either a supportive pressure, holding us up, or the other kind, squeezing the life out of us for the purpose of lubricating the larger machine. Different people can experience the same community differently. I recently saw a movie called TOMATO RED: BLOOD MONEY, that looks at a lot of these same issues of loyalty and belonging and rebellion quickly escalating into revenge and murder. It was harsh, but good; I recommend it.