The Mets have never loyally served Brooklyn as a team and that's particularly poignant with the Dodgers beating the Yankees this World Series. Nor will the Mets ever serve Brooklyn. They serve Long Island and Queens. Though Brooklyn boasts a land mass almost double Chicago’s and a population equal to Chicago’s — a city, by the way, with two teams — Brooklyn hasn’t had a team since Los Angeles stole the Dodgers. You start to wonder: could the Dodgers have been worth more simply by staying home? At peace with their true fans?

Could the Brooklyn Dodgers have been worth more money than the Los Angeles Dodgers?

Certainly it’s a question that would interest the likes of

, , , , and others of their ilk for various reasons. It’s an odd cross-section kind of question.So before one argues this is ancient, irrelevant history, it was at a recent Yankees game talking with a lifelong New Yorker that one of the authors realized how devastating losing the Dodgers truly remains in the living memories of those who grew up here in NYC. This particular New Yorker said losing the Dodgers was the hardest part of a tumultuous childhood: it was a fundamental betrayal of his town. Even Forbes has reported on this in the 21st Century.

It’s deep in there. Deeper, at least for this person, than the betrayals of his very own religious and educational institutions. Deeper than family hurts. Deeper than getting screwed out of business deals and getting the rug pulled out from under him by a foundation who had given a grant with strings attached.

Someone had stolen his childhood home team. Whodunnit?

Who stole the home team for whom, in Take Me Out To the Ballgame, we’re supposed to “root, root, root?”

The home team that Rome, in their classical prescription of wine and circus, thought would help manufacture regional conflict as a sort of pressure release valve on the steam behind popular uprisings — the very pressure that, at critical mass, moves the eyes of the populous towards their local and regional problems? You know, like both sides of the political divide did during the pandemic? Prior to any vox populi is the gustus populi and oculi populi: as go the eyes and taste buds of the people, so goes their voice and feet.

These days, this particular ex-Dodgers fan (you seriously think a native Brooklyner would still root for Los Angeles?) hedges himself against betrayal on the order of his home team’s magnitude. On the order of someone who stole his local colosseum.

Losing the Dodgers was the O.G. new city, new stadium deal. It’s not ancient history: not only are fans here still bitter because the oldest new stadium deal happened in their living memory, they’re bitter because that recent history keeps repeating over and over and over again. Now the St. Louis Rams. Now the Raiders. It’s a parroted tragedy that tries to proselytize our very American abyss of immense historical oblivion:

“To be American is to be the deracinated child of some other land or people or several other lands or peoples. Our own national identity is quite often a bright garish fabulous surface that we spread thinly over forgotten depths. Our national narrative is essentially an idea, never fully realized, of course, but able to keep us borne aloft above an abyss of immense historical oblivion.”

—

How much more so for American sports fans? Are we, like the oak trees that often fail to thrive in the planters of New York City, destined to be torn up by the roots and hope that merely some of us survive transplant? That some tree somewhere grows in Brooklyn? Say what you will of Manchester United Football Club, they were founded a hundred and forty-five years ago in the city that to this day bears their name. There they remain: the ancient Bowthorpe oak tree of soccer.

Do we have that in baseball?

The Cubs.

Beyond the North-Siders, the other two oldest teams were founded twenty to thirty years after the Dodgers and Cubs: the Yankees and Red Sox. Of course, as one reader pointed out, “oldest” teams is what he called a “sticky wicket.” Here we mean oldest in the sense of one location with consistent branding, but even that can get dicey. The Cincinnati Red Stockings were around since reconstruction and some Cincinnati Reds consider that their history, which can be debated. The Atlanta Braves started in Boston then went to Milwaukee now Atlanta: there are still grandfathers in Boston who lament them leaving in the same way Brooklynites do for the Dodgers. All of that said, the Yankees and Red Sox also happen to have two of the three highest fiscal valuations in all of baseball. They didn’t move. Say what you will about AT&T, but perhaps being one of the earliest stock tickers in existence (T) has something to do with ranking in the top 12 revenue-generating companies every year?

They’re still around.

Age before beauty and all that. And good — great — home teams are old. Sure, like some ancient trees, the richest ones might be hollow or dead inside, but on the surface an entire biome of fandom thrives off the heartwood of the dead. Old teams still get it done, soul-ful or soul-less.

At what cost would you sell your childhood home team to the other coast? Would you sell the Yankees to Seattle? Would you sell the Red Sox to Texas? Would you turn the L.A. Angels first into a basketball team and then merge The Angels with the New Jersey Devils? Is such a fall from grace worth such a Faustian bargain? At what cost would you sell Brooklyn of Jackie Robinson fame to Los Angeles?

A billion?

A trillion?

Is there a price?

Whatever the answer, we’re not asking the city government and franchise owners: we’re asking the fans.

It’s just that some government officials and franchise owners happen to have been fans, once upon a time. Do they remember what it means to be a fan for fandom’s sake? Do they remember what it was like when being a fan mattered more than the countless dollars that have allowed them to purchase the teams they now own?

Jackie stopped playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers the year Lance’s father was born and two years later, they sold to L.A. It’s interesting because his father died this past year and Lance has dealt with the administrative backlog that one dead fisherman stirs up in his wake. (Spoiler: it’s more mud than a catfish). At what cost of inheritance is it worth losing your childhood father? An unlawful death settlement? A 401k? A house?

Is there a price?

Lance would rather have his father back, living and well. Have him back than the forty hours on the phone trying to convince Computershare and E*Trade and Schwab to transfer three measly shares of Lowe’s into the estate account so he can liquidate it and cut a couple $200 checks to his siblings. How many degrading hours with lawyers haggling dehumanized death certificates and letters of offices does it take? Steve, his dad, died the exact same year Steve’s favorite football team, the Oakland Raiders, moved to Las Vegas. Lance would rather have his father back, the very father who would have rather had his Raiders back.

The man was born with the first new stadium, new team deal and died with a new stadium, new team deal. It is the trend that defines the boomer generation: world class products and profits over people. The momentum of that trend is a bear that first dies, then slows, then stops. Both ironically and coincidentally, if it isn’t stopped it will become a bear market trend.

What was the true cost of the sale of the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles?

When some business wants to unveil any missed potential gains from having favored one choice over another, they assess the opportunity cost. It’s not just what purchasing a stock costs you, it’s what purchasing this stock over every other stock you could have purchased costs you: the cost of hindsight when you bought Enron stock over Amazon. Do cities — or their rich citizens — do this when they purchase sports teams? If so, what city worries more about money than New York? What sports team garnered more feelings of betrayal than the time the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to L.A.?

Let’s run an analysis on the Brooklyn Dodgers’s opportunity cost, particularly since the Los Angeles Dodgers are allegedly the second-most valuable franchise in MLB.

Behind the Yankees, of course: the other non-Long Island New York team.

Right now, we have to beat the Los Angeles 2023 valuation of $5.24 billion.

Can we do it in that magical happy alternate universe where the Dodgers never left Brooklyn?

Could the fiscal opportunity of staying home actually have outweighed the fiscal opportunity of selling out to California?

The easiest place to look first is real estate.

At the time of writing this, there’s a new Jay-Z exhibit here at the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library from where I, Lance, type this line. The exhibit has, in many ways, made the library less functional for a time, but what it gave up in functionality it has paid back tenfold in borough pride here and abroad. Sort of the opposite of what happened with the sale of Ebbets field. Not five blocks from where I sit (as the starling flies) stands the marker for the old Ebbets Field, long lost home of the Brooklyn Dodgers. These blocks now have luxury high rises. They’re working on a massive overhaul here on Grand Army Plaza complete with restoration of the great limestone slabs that will slate over the once slattern cobbles that had dissolved into a half nakedness, clothed ever so sparsely by creeping wood sorrel, pokeweed, and pigweed. Not only does our library rival Chicago’s. It’s an area with a museum rivaling Chicago’s. A botanical garden that rivals St. Louis’. A decent zoo (happens to be my favorite, being a small town kid for whom all zoos are magical oases of safaridom, but my bride is from St Louis, so for her to compare the Prospect Park zoo to the Forest Park zoo is something like comparing a mosque in Dearborn to the one in Mecca). And a 150-acre old-growth wild forest mirroring the Adirondacks with a headwater for its waterfalls and sylvan eldritch wonders with elven names like Nethermead. In this arena of Brooklyn, city blocks go for $600-800 million. Considering Yankee Stadium covers four, a simple expansion would have easily put the property value in the $1.2 — $3 billion range. For the property alone.

But we don’t actually have to guess. Because when everything went down at the time of Smith’s death and O’Malley made his appeal to Smith’s widow, they started looking at property. He tried to convince the city to condemn what was then known as Times Plaza. He wanted to get them to commission a replacement for Ebbets Field.

Who rejected his proposal?

On the grounds that it would create a “wall of traffic?”

Perennial New York villain — and bane of the very rail system after whom the Dodgers derive their name — Robert Moses. Moses argued that a sports arena was an inappropriate use of the space.

70 years later, what did NYC do with Times Plaza?

We turned it into Atlantic Ave - Barclays Center, home of the Brooklyn Nets. Now, since I, Lance, watched the inaugural game there, I can easily say that the Nets are a wonderful Brooklyn team. The arena asked a bunch of independent Brooklyn restaurants to put up a second location inside Barclays. Again, I — Lance — write this mere feet from the Jay-Z exhibit as a migrant (though I have Brooklyn native family), but it’s easy to see the value the Nets brought home (though it took a few years). But let’s again think about long term teams, here. What is that plaza worth these days?

Total value is $4.9 billion — center is $1.29 billion in 2021 dollars, the Brooklyn Nets are valued at $3.2 billion. In terms of anticipated future gains, the Brooklyn Nets from 2003 to 2022 had an:

Investment gain of $2,982,000,000

ROI — 1,367.89%

Annualized ROI — 15.18%

Meanwhile, the L.A. Dodgers were valued at $4.08 billion by 2021. The L.A. Dodgers ROI from 2002 to 2022?

Investment gain of $3,640,000,000

ROI — 836.78%

Annualized ROI — 11.83%

In terms of anticipated future gains, 4% is a huge disparity where compounded interest is concerned.

At the Brooklyn Nets return:

15.18% annualized

$1.38 mil (the offer on the Dodgers) becomes

$13.47 billion

$4 mil becomes $39.045 billion

At L.A. Dodgers return:

11.83% annualized

$1.38 mil becomes

$1.97 billion

$4 mil becomes $5.7 billion

At the median rate between the Brooklyn Nets and L.A. Dodgers:

13.5% annualized

$1.38 mil becomes

$5.18 billion

$4 mil becomes $15 billion

Assuming they stay home and end up in the future site of the Brooklyn Nets, right smack dab in Downtown Brooklyn where all the subways now connect in Park Plaza, in 5 out of 6 models, the hypothetical 2022 Brooklyn Dodgers are worth more than the L.A. Dodgers. Only if we assume the worst case scenario of the purchase price and the worst annual average do we end up with a final dollar amount less than the L.A. Dodgers. To assume the 15% odds at the left, lowest end of the bell curve, that the least likely scenario on opportunity cost — being worth more in L.A. rather than staying home — seems a large enough cushion to envelope the new “home” team bias (survivor bias? Status quo bias? Shilling? Ageism? Observer expectancy? Funding bias? Implicit bias? All of the above?) Whose bias?

You L.A. Dodger fans who desperately want this to be wrong.

Why?

Because they’re your hometeam now and you desperately don’t want them to move.

Which yet again proves us right.

In another realm — social media — this desperation to preserve a community base and the equal and opposite disintegration of that community is what Cory Doctorow famously called “enshitification:”

“Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.”

— Cory Doctorow, Tiktok’s Enshitification

The same is true of sports teams. And we have dived headlong into the era of fully enshitified sports. First, the team is good to their fans and the fans build the fame of the team. Then, they abuse their fans to make things better for their business customers — the companies that buy ads, that buy ticket blocks, that buy box seats, that loan jets. Finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back value for the franchise itself. Then they sell to a new town and die. Sports enshitification. Welcome to the sewer. The water’s fine.

What’s a specific example of this enshitification?

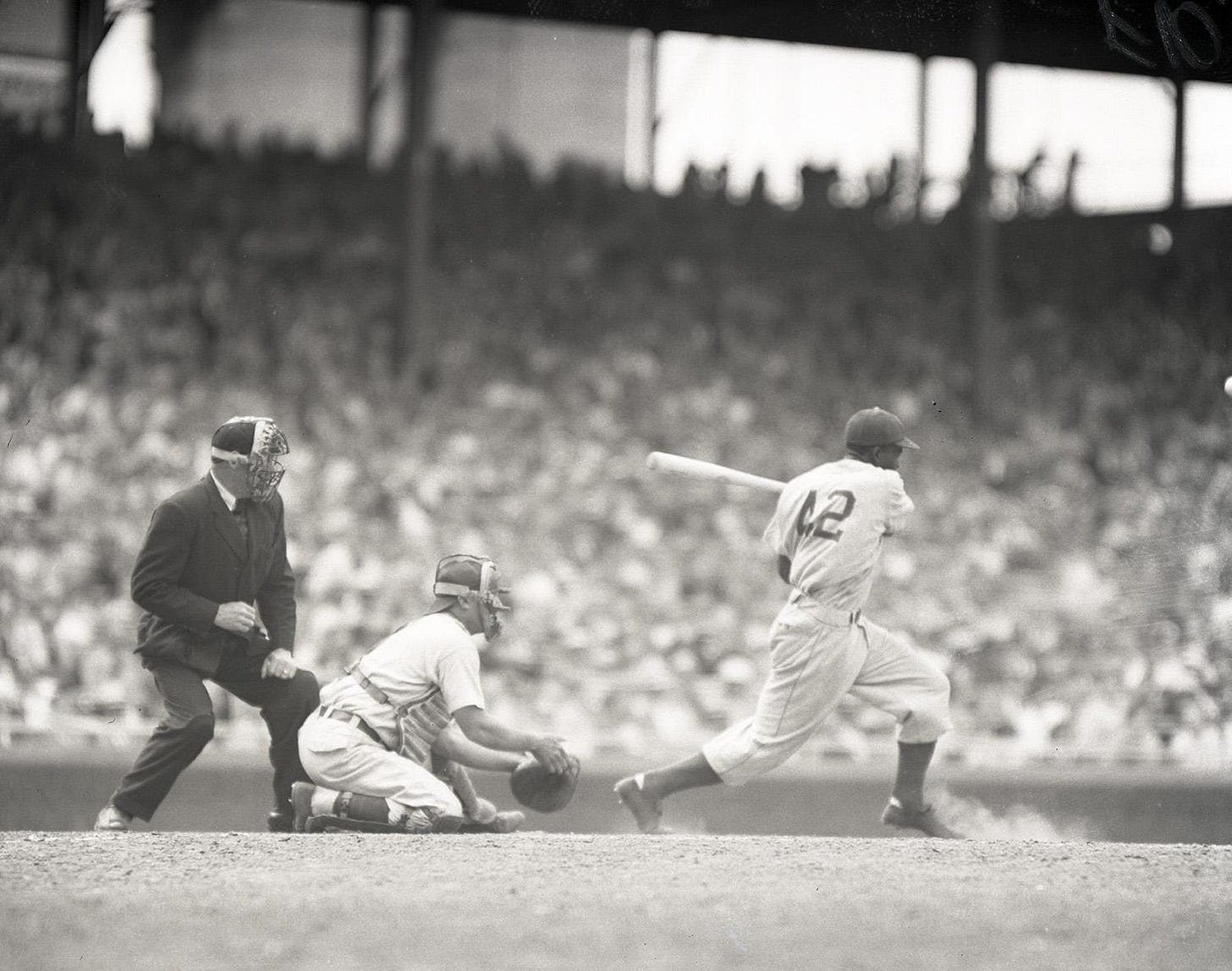

Jackie Robinson’s last at bat.

He struck out to end game seven of the World Series. The last World Series of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The Brooklyn Dodgers didn’t get another shot like the Cubs did. And the Cubs did. And the Cubs did. (Meet me in the end notes where I will repeat And the Cubs did 104 more times). California stole the Dodgers with the help of all of the accomplices above, stole — it’s quite easy to argue — those three World Series from Brooklyn.

You owe Brooklyn some trophies, L.A.

It wasn’t that last strikeout that knocked the wind out of Brooklyn. It was that there would never again be a series-winning at bat. Or any World Series at-bat for that matter. And after one final season, no more at-bats at all. And it’s not just at-bat stats and trophy wins. Consider the name itself.

The name of the Brooklyn Dodgers, as folks know, comes from the Trolley Dodgers: those who jumped in front of the rails to get to the stadium. If you’ve ever been to NYC or read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, you know New Yorkers will do anything in the traffic lanes to beat the crowd and get a couple more minutes with their family. They’ll jump in front of trains and hold open subway doors.

It’s not that Los Angeles had no trolleys when they moved. It’s simply that the same man — Robert Moses — along with the automotive lobby had started turning all the lines into bus lines in 1955. By the time 1963 came, there were no more trains in Los Angeles. Translation: nothing to dodge at all. They might as well have changed their name to the Los Angeles 405 and 101 Interchange Gridlock Honkers. For that’s what Moses did: Robert Moses sold our hometown subway team out to his idyllic town of grey cracked concrete and sable SUV smog.

So we’re starting a petition to change their name to the L.A Honkers. Sign your name here. An invasive species, migrating like Canadian geese, crapping all over everything good. Honkers. That’s right, we’re serious, sign the petition. We would love nothing more than for thousands of petitioners to rally around an absolutely ridiculous name change for L.A. Considering the theft, it’s the least we could do.

I mean this is a region who has imported everything from beaches to water because they live in valley that wants to be a desert, a region experiencing real, godawful drought. This very same desert locale bought out a Minnesota team named The Lakers. Raindancers may have been more appropriate. Or inappropriate as the case may be.

Then again, we live in the world where McDonald’s no longer uses beef tallow for their once famous fries, Wal-Mart no longer has walls, Blackstone buys out historically black neighborhoods, and Twitter rebrands as a porn star. Why not let the land of automobiles keep our subway name?

Meaningless, meaningless…

Prior to the 2015 World Series, a mutual colleague of ours once said that the Cubs might never win, but they played in hopes of a sort of apocalypse: an unveiling of the veil of baseball’s shadow unto truest reality wherein they win again and again for diehard fans who have been wandering in the wilderness all those years, who died in hope of the promise, who saw it, welcomed it from far off, but never themselves set foot upon that final destination. Something like faith: that it’s a fantasy for the Chicago Bears to win the World Series, but that the Cubs winning the Series was true faith because it was logically possible.

Will Los Angeles ever give up the Dodgers?

Perhaps that’s the wrong question. Or not the only one to be asked. (Though it is logically possible and could therefore constitute a true kind of faith, a true kind of hope, though currently unseen).

For in a similar way to the Cubs of 2012, perhaps there lies a section of the New Heavens and New Earth where the original Brooklyn Dodgers play for the original Dodgers fans game after game after game. At least that seems to be the belief of the writer of Field of Dreams.

Rather different end goal when compared to a Field Audit, ain’t it?

It’s certainly worth a second petition: that we in Brooklyn get our team. By the time any plans manifest, it will have been as long as the Cubs waited for a World Series. We don’t need two teams like Chicago.

But, since Brooklyn’s the same size as (or arguably bigger than) that great city, one baseball team would be nice. Just one. Sign here.

We stand in that apocalypse. In a world of deracinated children of long dead sports fans or teams or even several long dead sports fans or teams. Our sports identities have become the bright garish fables slathered like sequin paste over the abyss of immense historical sports oblivion: the enshitification of our manufactured regional conflicts. Rome had wine and circus, but our Little Egypt prairies and orchards now lay fallow with inedible Monsanto corn and our circuses change with the flick of a willow switch. When we shut them down, we have almost no faithfulness left to keep our attention locally. And so we focus on our regional problems and take to the streets, take to the capitals, protest nonviolently and, when unheard as Dr. King once said, even riot. Perhaps this is a rebuke of wine and circus in general — that we shouldn’t have them. That we should face and then fix our problems slowly, steadily. That we should elect a woman who was good at running the sewage department for mayor and not a real estate profiteer who criminalizes poverty, clutters our skies with dystopian drone police, and publicly praises himself at every turn. That we should actually solve our injustices, not find entertaining “representative” figureheads who make them worse. Maybe we shouldn’t have wine and circus. Maybe we should face and fix our problems slowly, steadily, and write our regulations in the steady drip of blood rather than the gush of a riot.

If sports has any virtue, that’s its one silver bullet: that it’s allegedly meant to keep the Pax Americana. To release the steam pressure of regional conflict.

But we Americans have stroads where Rome had roads and streets. We have new city, new stadium deals, whereas multiple colosseums still stand to this day. I hear Rome made their concrete of limestone powder, limestone chunks, and sea water so that it self-heals. Ours crumbles in fifty years. And so do our sports teams. We make our concrete that way because it has a higher profit margin. At least in the short term.

But the funny thing is, long term it’s actually worth less.

And so are our sports teams when they sell to another city. It literally defeats their entire stated civic purpose. And without that proximate good — one that’s dubious at best — what the hell are they good for?

Bottom line? The short term almighty dollar is worth infinitely more to owners than an army of lifelong fans and the infinite-sum game it implies. And that's why the opportunity cost of the Brooklyn Dodgers isn't just that the owners and cities missed out on billions of dollars of revenue. That the Raiders missed out. The Rams. No. They missed out on the loyalty of the very fans that, when local sports shut down, come face to face with regional conflict and, after they meditate on it for awhile and find themselves left without a chance for reparations, riot. Lance isn’t a sports fan because he abhors wine and circus: he thinks sports slap bandaids on injustices. But Isaac is a sports fan. And if the Pax Americana is the main virtue of modern sports, then perhaps faithfulness — not mere loyalty to a person or a place, but a higher loyalty to principle — is the opportunity our discord lacks. For hope that is seen isn’t hope. Who hopes for what he already has?

But if we hope for what we do not yet have, we wait for it patiently…

Well researched and expressed! An article any true sports fan will respect. Hoo-rah!