The Economy of Stories in The Name of the Wind

Reflections on the self-made character and the kenosis of the author.

Few modern epic fantasies have captured the hearts, minds, and imaginations of current readers quite like The Name of the Wind, even including A Song of Ice and Fire and Sanderson’s oeuvre. Part of that is because to a greater degree Martin, Hobb, and Abercrombie — to a lesser degree Rothfuss — essentially carried on what Tolkien wisely stopped: a sequel to The Lord of the Rings focused on the exceedingly dark side of humanity:

I did begin a story placed about 100 years after the Downfall, but it proved both sinister and depressing. Since we are dealing with Men it is inevitable that we should be concerned with the most regrettable feature of their nature: their quick satiety with good. So that the people of Gondor in times of peace, justice and prosperity, would become discontented and restless — while the dynasts descended from Aragorn would become just kings and governors — like Denethor or worse. I found that even so early there was an outcrop of revolutionary plots, about a centre of secret Satanistic religion; while Gondorian boys were playing at being Orcs and going around doing damage. I could have written a 'thriller' about the plot and its discovery and overthrow — but it would have been just that. Not worth doing.

Letter 256, (dated 13 May 1964)

Fifteen months before dying, Tolkien added:

I have written nothing beyond the first few years of the Fourth Age. (Except the beginning of a tale supposed to refer to the end of the reign of Eldaron about 100 years after the death of Aragorn. Then I of course discovered that the King's Peace would contain no tales worth recounting; and his wars would have little interest after the overthrow of Sauron; but that almost certainly a restlessness would appear about then, owing to the (it seems) inevitable boredom of Men with the good: there would be secret societies practising dark cults, and 'orc-cults' among adolescents.)

Letter 338, (dated 6 June 1972)

But the darkness isn’t sufficient to explain The Name of the Wind, mindful of the wiccan alchemical epic horror that it is.

Why then the popularity?

Part of it is because, like Peter Beagle did to the fairy tale before him, Rothfuss uses his take on the epic fantasy to talk about the economy of stories, who gets to tell them, how, what is considered truth, what’s considered a lie, and what the epistemological quest of the very world may or may not yield to us on proper searching: when a man whose name means “to know” finds out if he even knows himself, let alone the fundamental structure of reality, society, history, science, etc. Combine that with a lovable rogue in a Spanish-style picaresque, and you end up with a recipe for turning lead to gold.

I don’t want to spoil much of the book, but what I can say is it begins by subverting every DnD campaign ever: instead of a bunch of adventurers meeting up in an inn or tavern and getting some information out of the innkeeper to begin their epic quest, it starts at the long end of a quest with the innkeeper getting some information out of green adventurers.

The innkeeper is landlocked. Perhaps by his choice. Perhaps by his circumstance.

As it turns out, he’s become — either figuratively or literally — a bit of a myth. You really, at this point, should read the book. Particularly if you care about spoilers.

But I’m going to continue for those of you who have already read it and also for others who either won’t ever read it or don’t care about spoilers any more than I do or the opera community does. Kvothe — the innkeeper — is found by a debunker. A demythologizer, more accurately, who turned the mythic dragon into merely a fire breathing lizard in his Mating Habits of the Common Draccus. It’s a different kind of lie, that brand of demythologizing cynicism. As Tolkien said:

He who breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom.

In other words, that butterfly corpse you’re busy pinning to styrofoam isn’t a butterfly. It’s the corpse of a butterfly. A butterfly is a living creation that will not remain such while being mothball murdered, stiffened, flattened, and then pinned with little metal pins to screeching white foam that will itself never decompose. The demythologizer dissects and vivisects, ruining the whole of the creature before them. The myth maker makes a whole out of unconnected parts. One rumor makes molehills out of mountains. The other makes mountains out of molehills.

Neither tell the truth of things.

The curious thing is that this story has a frame narrative much like 1001 Nights or, more likely, the Panchatantra and their चान्द्रायण (cāndrāyaṇ). In any case, there’s this man who comes to get Kvothe’s story and that entire frame. Then there’s Kvothe’s story told in first person perspective… which is an autobiography about a man who chases stories, finds fae creatures, learns their stories… and you really aren’t quite sure where one begins and the other ends. It’s a continuum of narrative, sometimes with thematic jumps so blurry, you’re unsure how they’re effecting and affecting one another.

That’s kind of the point.

The debunker’s name is Chronicler:

Chronicler refused to back down. “Other people say you’re a myth.”

“I am a myth,” Kote said easily, making an extravagant gesture. “A very special kind of myth that creates itself. The best lies about me are the ones I told.”

“They say you never existed,” Chronicler corrected gently.

Kote shrugged nonchalantly, his smile fading an imperceptible amount.

In this case, I’m thinking Kote’s telling the truth. Strictly speaking, a myth that creates itself is a creation myth. It’s a metaphysic, in a way.

Sensing weakness, Chronicler continued. “Some stories paint you as little more than a red-handed killer.”

“I’m that too.” Kote turned to polish the counter behind the bar. He shrugged again, not as easily as before. “I’ve killed men and things that were more than men. Every one of them deserved it.”

“Some are even saying that there is a new Chandrian. A fresh terror in the night. His hair as red as the blood he spills.”

“The important people know the difference,” Kote said as if he were trying to convince himself, but his voice was weary and despairing, without conviction.

I take this at face value, honestly. Chronicler’s job is to inspect myths and if not deconstruct them, at least get to the reality behind them. Demythologize living myths. So I’m assuming he’s trying to demythologize the Chandrian — the demon boogey man, those moon cycle watchers — in Kvothe, who may or may not be one now.

This is a book written by the person whose favorite book is The Last Unicorn by Beagle. Let’s assume for a moment that this book functions similarly: parodying in a Nabokovian sense the epic fantasy with epic horror.

Chronicler gave a small laugh. “Certainly. For now. But you of all people should realize how thin the line is between the truth and a compelling lie. Between history and an entertaining story.” Chronicler gave his words a minute to sink in. “You know which will win, given time.”

The line’s thin. And Chronicler knows the difference.

Chronicler took an eager step forward, sensing victory. “Some people say there was a woman—”

“What do they know?” Kote’s voice cut like a saw through bone. “What do they know about what happened?” He spoke so softly that Chronicler had to hold his breath to hear.

“They say she—” Chronicler’s words stuck in his suddenly dry throat as the room grew unnaturally quiet. Kote stood with his back to the room, a stillness in his body and a terrible silence clenched between his teeth. His right hand, tangled in a clean white cloth, made a slow fist. Eight inches away a bottle shattered. The smell of strawberries filled the air alongside the sound of splintering glass.

In this instance we see exactly why Kvothe finally decides to tell his story.

Here, Chronicler is afraid. Of what? Being caught inside a story. Rather fascinating fear for a demythologizer. And this is what one PhD candidate (whose article I cannot find for the life of me, I’ll comp a free year paid subscriptions to anyone in the comments who can find it) called “the economy of stories” in The Name of the Wind.

The big academic word is “transdiagetic metalepsis” among a text’s dream and story levels. Something like the personification of Personification, the narrativizing of Story per se. If Story stops telling the story, then the story stops and therefore Story stops. Silence enters. The being of Story is compromised. Kvothe, the name, means “to know,” but knowing and speaking and a spell all come from the same word. Gospel is, after all, an Old English version of “good” and “news.” So there’s a sense in which a retelling of this man’s book of deeds is both the gospel truth and a spell: but which is which? And how does his most precious self — the speaking, spelling thing named Kvothe — hang on the very word of the story?

I must, here, take an obligatory break for an excerpt from the following poem:

As Kingfishers Catch Fire

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell's

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells...In a book about names, I find that phrase “myself it speaks and spells” particularly illuminating for a man who seems unable to remember his true name.

So yes, on the economy of stories and transdiagetic metalepsis among a text’s dream and story levels, James Paxon in the Poetics of Personification calls these three layers: diegetic (narrator level), mimetic (line of action), metadiegetic (the narration about the narration).

This is where it gets interesting:

“The ostensible transgression of a personification figure into the metadiagetic level, or of a human figure into the diagetic level, would involve, to borrow further from Ginette’s taxonomy, a transdiegetic metalepsis.” Gennet defines a narrative metalepsis as the direct intermingling or collapsing of the elements belonging to two distinct levels of diagnosis. A character who emerges from a book or painting within the narrated universe of a particular novel involves one kind of metalepsis. Another would involve a narrator, like Tristan Shandy, who urges us (presumably outside or “above” the primary line of diegesis) to produce a direct effect on one of his characters — like closing the door to Walter Shandy’s room…. The metaleptical effect becomes a macrometaphor of personification fabulation itself. (77)

Later Paxon says:

“Chaucer’s human characters are diegetically removed from the active and vociferous personification figures who people the primary field… we are faced with a peculiar structural relationship between mute, frozen, and lifeless beings who are makers (epic poets) and active, loquacious lifeless beings who are made (personified verbal utterances). Whether we consider the enshrined writers as ekphrastic elements narratologically quarantined from the personification figures, or as ontologically diminished human consciousnesses in direct physical proximity to enlivened personifications, we readily apprehend the text’s deft and radical ironizing of the problem of literary character differentiation. The makers become the made; the made things gain the power and vitality of human makers.” (85)

“…In The Parliament of Fowls, Chaucer provides another narrator who suffers from artistic and intellectual aridity. The poem begins with a bald paraphrase… this artless paraphrase has prompted critics to see the central theme in the Parliament as a meta poetic self-inquiry carried out by Chaucer into the problems of making poetry. The narrator’s self-doubt about his powers as a poetic maker are amplified by the unusual structural and formal features of the poem.” (86)

The poem has a gate that, depending on the side of the gate, could read as the gate of heaven or hell. Kind of like the door of stone.

Basically because the gate refers to the reading of the text, it’s a verbal artifact within the primary diagesis, making a meta diagesis — a narrative text “within” a narrative text.

Once inside, there are gobs of classical epic, Arthurian Romance, and Roman history characters on the wall — the narratological space excluding personification. Making a meta-metadigesis — a story within the story within the story. Chaucer separates historical figures who are dead from the author from the personification figures from the objects.

And so Chaucer’s “poem charts a gradual reduction of the prospopoetic powers among the human characters and a runaway increase of it in the personifications.” (88-89)

Sound familiar?

A myth that makes itself?

As Kvothe tells the story, Chronicler is growing silent and Kvothe is stealing his power of narrative, taking back the story: literally creating himself from the mythopoetic powers he has as King of Sun and Shade.

In some ways, this shows the life cycle of language, a name, a myth — from poetry to prose and back again. As George MacDonald said in The Imagination: Its Function and Culture:

“All words, then, belonging to the inner world of the mind, are of the imagination, are originally poetic words. The better, however, any such word is fitted for the needs of humanity, the sooner it loses its poetic aspect by commonness of use. It ceases to be heard as a symbol, and appears only as a sign. Thus thousands of words which were originally poetic words owing their existence to the imagination, lose their vitality, and harden into mummies of prose. Not merely in literature does poetry come first, and prose afterwards, but poetry is the source of all the language that belongs to the inner world, whether it be of passion or of metaphysics, of psychology or of aspiration. No poetry comes by the elevation of prose; but the half of prose comes by the “massing into the common clay” of thousands of winged words, whence, like the lovely shells of by-gone ages, one is occasionally disinterred by some lover of speech, and held up to the light to show the play of colour in its manifold laminations.”

How does this play out in the history of texts?

I have coined the word “auctophany” to indicate the presence of a narrator in his own text. That can happen in the general aspects of the subcreation, sans direct incarnation of the author’s person. Or it can happen more specifically as an incarnation of the work’s authority. Sometimes the author shows up in a literal presence, the auctophany per se. But subcreation is the general incarnations of thought in the work. Imagination — even in our dreams — form the very structure of our thought: in fact dreams figure reality so that the line between our dreamt imaginations and our waking world blur as they inform one another. Later in his work on dreams, Synesius expands on his understanding of what this imagination offers us, for good or ill:

Nature has poured the richness of the imaginative essence into many parts of existing things; it descends even to the animals which have as yet no understanding, and is no longer the vehicle of the more divine soul, but itself rests upon the forces beneath, being itself the reason of the animal; and many things this creature thinks and does befittingly through its agency. Thus a cleansing takes place even in creatures without reason, with the result that a better force enters in. Whole races of demons also have their existence in such a life as this. For whereas these throughout all their being are phantasmic, making their appearance as images in things that are coming into being, in the case of man most things come by imagination and that alone, though in truth a good many in company with another, for we do not form thought-concepts without imagination, unless it so be that some man in a rare moment of time grasps even an immaterial form.

To go beyond the imaginative would be no less difficult than happy to achieve. "For", the master says, "happy the man to whom understanding and prudence come even in old age," speaking of prudence bereft of imagination. But the life in question is founded on imagination or on that intellect which makes use of imagination. This envelope of soul-matter which the happy have called the enveloping soul, is in turn god, demon of every sort, and phantom, and in it the soul pays its penalties, for the oracles are agreed about this, to wit, the similarity of the soul's way of life in another world to the imaginings of the dream condition; and philosophy concludes that our first lives are but the preparation for second lives, and that the best conduct in the case of souls lightens it, whereas the worst imparts a stain to them.

[“Synesius, Dreams 3 - Livius,” accessed April 5, 2020, https://www.livius.org/sources/content/synesius/synesius-dreams/synesius-dreams-3/.]

He's arguing first that we humans can’t even properly think without incarnating ideas via the imagination, that our wills are predicated on the minor wills inherent within imagination, again for good or bad: that the very real realm of conscious ideas and superintelligences (i.e. of angels and demons) functions in the realm of the imagination. Very real imaginative wills could hijack our minds for good or bad. In a parallel to Synesius’s dream commentary, Macrobious in his Commentary on the Dream of Scipio shows how the somnium represents meaning to the dreamer. “There are five varieties of [somnium]: personal, alien, social, public, and universal. It is called personal when one dreams that he himself is doing or experiencing something; alien when he dreams this about someone else; social when his dream involves others and himself….” Michael Zink in his The Allegorical Poem as Interior Memoir points to this passage:

The somnium publicum is a dream which has a public place for its setting, the somnium generale, a dream characterized by the intervention of parts of the universe, such as the sun, the moon, the stars, etc. Thus the criterion for classifying the different kinds of somnium is the dreamer’s presence or absence as an actor in his own dream, from the most intimate kind, which he fills entirely, to the most general kind, offering a panorama of the universe from which he is totally absent.

[Michel Zink, Margaret Miner, and Kevin Brownlee, “The Allegorical Poem as Interior Memoir,” Yale French Studies, no. 70 (1986): 106-107, https://doi.org/10.2307/2929851]

The assumption of the latter being, of course, that the universe is speaking to him, to borrow the parlance of certain upstate yurt-dwelling hipsters. In all cases, then, the dream — which Synesius rightly assumes is identical with imaginative literature — takes place in the mind of the maker, the dreammaker in this case. So even the sun and the moon and the stars interact as a sort of incarnation of the dreamer. Zink argues that the dorveille posture assumed is a sort of dreamlike state that the creators would enter in order to create their works, something that Paxon picks up on as well. But while Paxon focuses on the description of it — and its effects on personification — Zink later points to the original meaning of rêver:

to wander about both the mental and physical countryside: it is the activity of the horsemen and, during the same interval, of [Guilluame IX, the first troubador’s] mind. Under these circumstances, the relation between the literal and the figurative sense of rêver is a relation both of simultaneity and of causality. As for the result of the daydream, it may be designated equally well as the conclusion of the horseback ride — the arrival in another world —, as the affective state and the imaginary aspect of the dream — the amorous ecstasy — as the poem which may involve both the one and the other, and which defines itself literally as the product of a waking dream.

[p. 109]

On the negative side, it reminds one of the fictions told in Vanilla Sky, which focused on lucid dreaming and its interplay with fiction and the stories we tell ourselves: open your eyes, David, who incarnated himself in his own little world of a dream. Or perhaps the similar theme in the film Memento, who killed to forget his fantasy was a fantasy. “In every case, an impression or a preoccupation which haunts the wakeful poet at the poem’s beginning, finds its correlative, its prolongation, its fulfilment or its explanation in the vision which comes to him.” Zink shows how the “interweaving of interiority and exteriority” project outward the thoughts of the author’s mind in specific incarnations within the author, the dreamer.

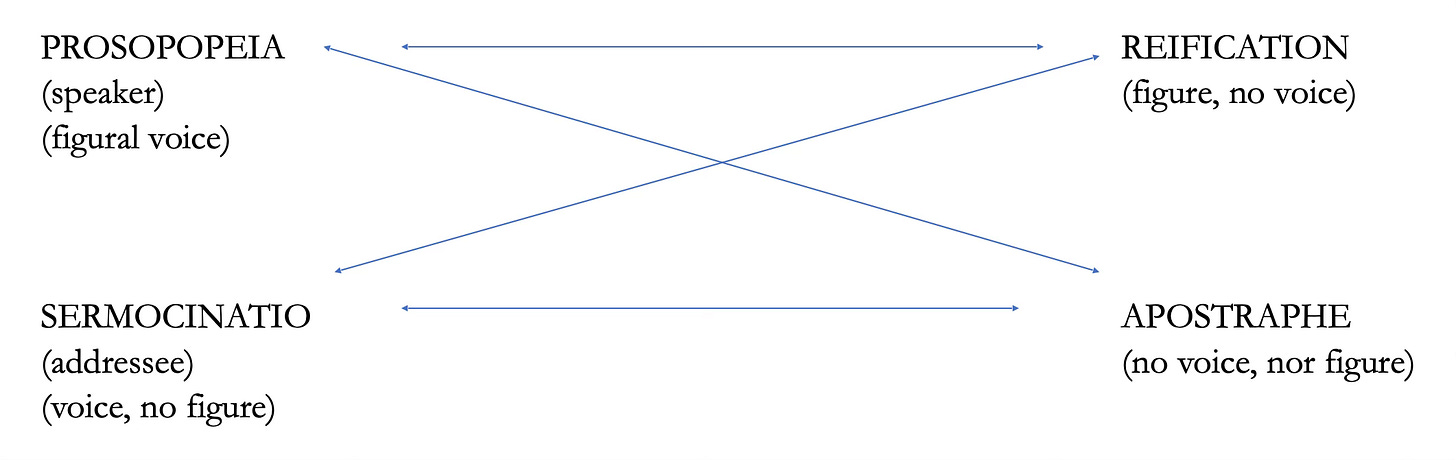

Sometimes the poet encounters an interior thought that leads him on an exterior adventure, sometimes an exterior encounter that leads him on an introspective pilgrimage, but the twin consubstantialities remain. Paxon mimics this when he points first to the O.G. allegory, the Psychomachia, which is bad literature… unless its entire point was an experiment demonstrating what is literarily possible within the allegorical genre. In that case, it is sui generi. From this genius, Paxon calls personification “an imbued, privileged macrofigure, a meta- or super-trope” and “a prime poetic mark of rhetorical self-awareness and maturity, a signal not of the failure of the literary imagination, but of its success and fulfillment.” He even points out the use of the personification of Personification in the Fairie Queen by Spencer as proof: it’s the incarnating of specific thoughts in images that makes up any given work of imaginative literature. He makes a sort of Greimas square (Aristotle’s square of opposition) to show the geometry of relations as we move from interior to exterior encounters, from voiced to unvoiced, from the figural mimetic to the literal diegetic:

Where prosopopeia and reification are contraries on the spectrum of diminishing to increasing figural speech. Apostrophe marks the corollary, but not inversion of prosopopia. Sermocinatio is a corollary of reification. So a personification, then, is a figural voice (Death came and said, “Be healed”). Reification a figure without a voice (these seven hills are the Body Politic). Sermoncinatio is a voice without a figure (a voice spoke from heaven “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased. Listen to Him.”). And apostrophe is either the addressing of an inanimate object or — more likely — the personification of a once-present, but now-not-present human (Hamlet talking to a skull).

Paxon then reconfigures this in his conclusion into something like this:

He elucidates it thus, speaking specifically of Error a.k.a Folly:

Spensor’s Error in The Faerie Queen signals “the deconstruction of textual presence.” That is, the peculiar narrative scene of the figural character’s unmaking posits that even “unmade,” she still exists as a palimpsest, as a present absence or an absent presence. This paradoxical state of affairs tacitly designates the condition of all personification characters. The Faerie Queen presents a reminiscent absent-but-present personification at the end of the poem. Arriving at the rear of the procession of hours, months, and season in the “Mutabilitie Cantos,” Death appears well outside of his tradition iconographic agency (see Macey 45-47), seeming to defy description:

And after all came Life, and lastly Death; Death with most grim and grisly visage seene, Yet is he nought but parting of the breath; Ne ought to see, but like a shade to weene, Unbodied, unsoul’d, unheard, unseen… (vii.46)The rhetorical question about the parting of breath ambiguously marks Death not just as his real signified (“death” — the moment of human expiration) but also as the authentic phenomenal character of his status as a textual signifier: the illusory character “Death” is no more than a jet of air laryngeally formed. …More intriguing, though, is the personification’s virtual invisibility and intangibility, his phenomenal status as an absent presence or present absence. Milton’s Death in Paradise Lost also (un)exists according to this kind of descriptive obscurity:

The other shape, If shape it might be call’d that shape had none Distinguishable in member, joint, or limb, Or substance might be called that shadow seem’d, For each seem’d either; black it stood as Night, Fierce as ten Furies, terrible as Hell, And shook a dreadful Dart; what seem’d his head The likeness of a Kingly Crown had on. (II.666-73)

Structurally, Error and the two Deaths represent a set of coded personificational variants that includes, as its preliminary subsets, the “first personifcation” and the “second personification” explained in chapter 2. The total set of coded variants includes, among other variants, a modified (meta)personification in which the text records a narrativization of the making or unmaking (for example, the destruction of Prudentius’ Vices) of a prosopopoeia character’s rhetorical structure (the personifier/personified dichotomy). Spenser’s Error involves this narrative move and the subsequent narrativization of characterological absent presence/present absence. The two Deaths of Milton and Spenser, however, indicate a narrativization only of the absence-presence paradox. Each particular example here is under-written by a distinct poetic code, a code controlling a respective subset in the whole set of personifcational varieties.

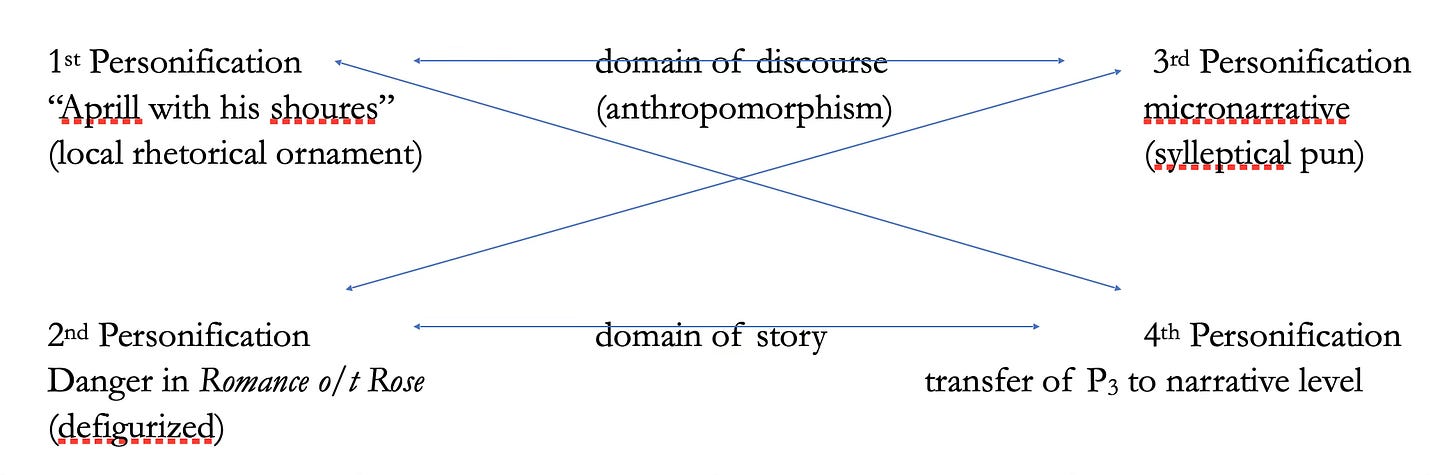

A reordered taxonomy along with an illustrational calculus of varieties will help explain the codes in schematic terms [in the Griemas square above]:

We can designate as P1 the “first personification,” that is, the variety that is local rhetorical ornament. P1 = (pr/pd)(D), where “D” is the domain of discourse. On a parallel line with David Dawson’s distinction of basic personification vs. narrative allegory, John P. Hermann calls this effect a “microallegory.” Example: “Aprill with his shoures.”

In the “second personification” a P1 is defiguralized or literalized; what existed solely on the level of discourse now exists on the level of story. This modification can be schematized as P2 = (pr/pd)(S), where “S,” or narrative “story level,” is the domain in which the homology exists, gets distributed. As in the first calculus, pr = the “personifier,” pd = the “personified.” (Examples included all actantial characters like Danger in The Romance of the Rose or Bunyan’s Despair in The Pilgrim’s Progress.) The trope “anthropomorphism” may be a categorial hybrid of or bridge between P1 and P2.

Both P1 and P2, however, differ only in terms of narratological actantiality: their difference is governed by the putative separation of discourse from story as well as by the syntagmatic modulations of narrative tempo (see above, chapter 2). Essentially, the two personifications’ signifieds (or personifieds) can be the same: abstract ideas, institutions, human mental faculties, inanimate objects, etc. The poetic potential thus exists for signifying the very semiotic structure of personification itself as a personified. When this is accomplished sheerly on the level of discourse, a variant evolves that we can think of as a “third personification,” or P3. These are not fully materialized or literalized instances of the elementary structure pr/pd. Rather, pr and pd are not fused into a homological pair, but are heterological components that get distributed in the domain of discourse as elements. The heterology signifies the idea of the semiotic power whereby the hology is made: (pr+pd) (D). A P3 can entail an elaborate micronarrative comprising ornamental metaphors and similes of encasement or eruption, as in the scene from Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde where Troilus is described by the narrator as metaphorically similar to wood encased in bark and as a tree losing its cover of leaves (iv. 225-31). More commonly, however, it involves the use of semiotically programmatic words like “embody,” “enclose,” “uncover,” or “deface” in the verbal context of a P1. The programmatic word works like a sylleptical pun to foreground the imagery of insides/outsides, faces/masks, minds/faces, ets. (Examples: Criseyde’s promise to Troilus that Fortune will not “deface” her fidelity, Troilus and Criseyde IV.1682; Duessa’s flattery that Night “can the children of fayre light deface,” The Faerie Queene, I.V.24; Prince Arthur’s similar claim that Night “doest all things deface,” FQ III.IV.56.)

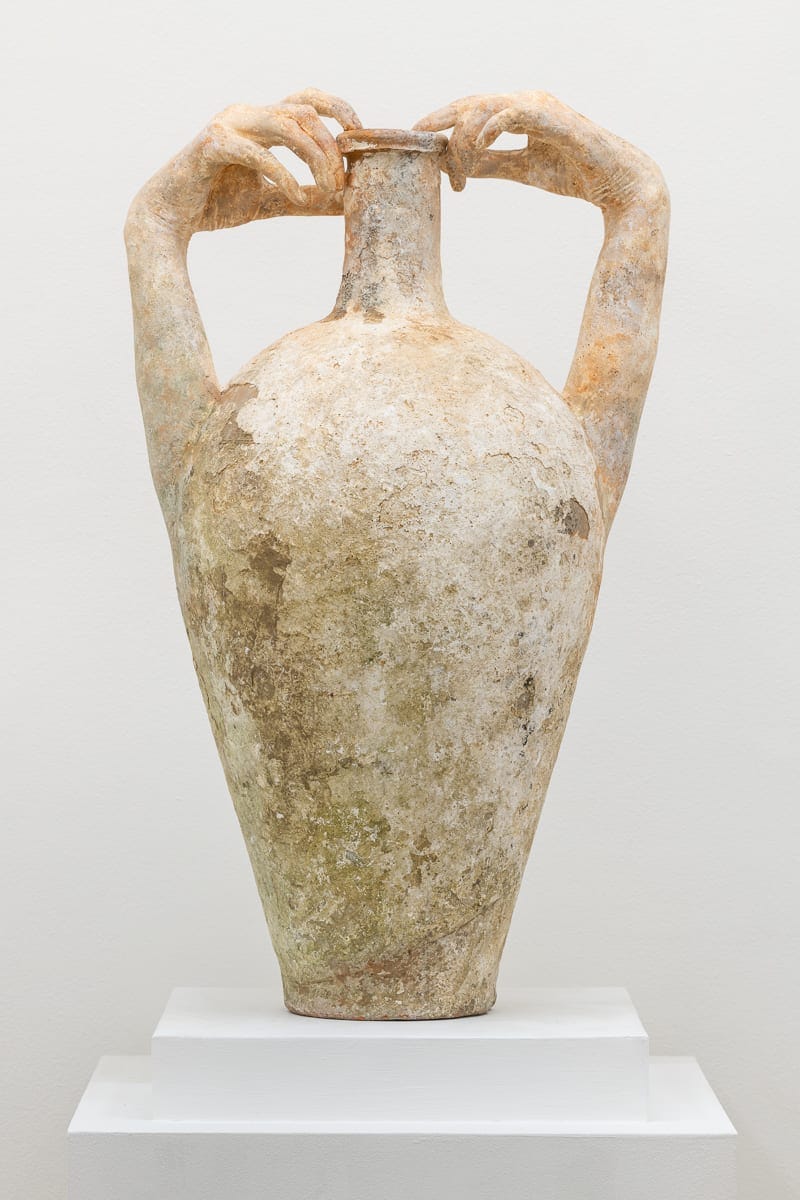

The full-scale narrativization in the primary diagesis of the elementary pr/pd, structure instantiates a P4, the “fourth personification.” More precisely, the effect can be schematized as the transferring onto the level of narrative story a discourse-level P3, that is: (pr+pd) (S). For J. Hillis Miller, the narrativization of personification’s elementary semiotic structure assumes literary vitality in the topical scenes of magical human making or unmaking. The tale of Ovid’s Pygmalion and Galatea visualizes the magical prosopopoetic process directly; it is a dramatic parable for all poetic personification (Pygmalion 6). Conversely, other Ovidian metamorphic tales, like the detailed reificational conversation of Myrrha into a tree or of the Propoetides into stone statues directly dramatize the prosopopoetic unmaking (Pygmalion 5-11).

He includes later as an example Ovid’s tale of Myrrha:

nam crura loquentis terra supervenit, ruptosque obliqua per ungues porrigiturs radix, longi firmamina turni, ossaque robur agunt, mediaque manente medulla sanguis it in sucos, in magnos bracchiad ramos, parvos digiti, duratur cortice pellis. Iamque gravem crescens uterum perstrinxerat arbor pectoraque obuerat collumque operire parabat: non tulit illa moran venientique obvia lingo subsedit mersitque suos in cortice vultus.

(x.489-97)

(For even as she spoke the earth closed over her legs; roots burst forth from her toes and stretched out on either side the supports of the high trunk; her bones gained strength, and, while the central pith remained the same, her blood changed to sap, her arms to long branches, her fingers to twigs, her skin to hard bark. And now the growing tree had closely bound her heavy womb, had buried her breast and was just covering her neck; but she could not endure the delay and, meeting the rising wood, she sank down and plunged her face in the bark.)

As myrrha is reified or dispersonified, the narrator characterizes the actual event with images of physical encasement. Myrrah’s limbs do not just change into branches and shoots; the earth covers her feet, and the bark of the tree grows around her torso, neck, and face. The sequence of reification is governed by the same metapoetic code that underwrites the destruction of Orgoglio, even though Orgoglio exists as a genuine personification character before his unmaking, and Myrrha is a woman before her magical undoing. This variation of metapersonfication (or metareificaiton) involves narrativization of the creative or destructive act and materialized imagery of the pr/pd structure, minus the paradoxical presence/absence residue.

…personification is governed by a series of codes founded upon a common set of logical propositions. The taxonomy of this concluding chapter does not claim utterly to exhaust personification’s potential representation in an extended series of coded calculi (above all, I stress that the calculi primarily serve an illustrative purpose). But another variant of metapersonification concerns the phenomenological status of the whole literary text that is consequently rendered self-reflexive by the interdependent operations of the codes heretofore described. The intensely self-reflexive character of the literary texts examined in this book implies a further dimension in personification and allegory theory. When we speak of a narrative text that is “self-reflexive,” “self-referential,” or “self-conscious,” we employ metaphors that figurally imbue the text with its own sentience. Narratives that thematize their own poetic creation and form are seen to “turn back” on themselves; they “reflect” upon their own ontological natures. This metaphorical characteristic is the simulacrum of human consciousness.

[James J. Paxson, The Poetics of Personification (Cambridge University Press, 1994) 54ff; 160ff]

Long walk to get to that part of the quote, but that right there is precisely what I’m driving at: the mind not only divides into loci and personifications spread through out the various plot points on the spectrum between personification and dispersonifcation. It also, when it reflects on that process, can become, if it isn’t in vain, self-conscious. The character’s will may merge with the Author and fulfill its ultimate ends and is, in fact, finally free. Having chosen “the Good” of the Idea of the Author’s story, the character (including partial or total auctophany per se), the totality of the subcreation (auctophany in general), and the reader (the fandom of the author) in experiencing both helps them merge with the writer’s own human consciousness as a simulacrum.

Mindful of this — the economy of story and its specific examples in the personification and reification spectrum of both Error (Folly) and Death — I believe it’s for this very reason that Rothfuss invented a variation on the etymology of “quothe” in Kvothe and originally rejoiced that no instance of the word “Kvothe” existed on Google: he invented a name that has now ossified, that has become Kote the man waiting to die in the inn at the start of The Name of the Wind. He has demonstrated through his career the lifecycle of a word from mythopoetic verse to demythologizing academic prose. (Sorry for driving the last nail into the coffin here, Pat, but I hope it honors your work in a kind of eulogy). Marquez at this point through his work would simply deal with prose, with the dying of language and imagination. Tolkien — even Coleridge — and especially MacDonald would focus on the esemplastic nature of it. Rothfuss’s Kingkiller Chronicle illumines the transition from the latter towards the former.

A theoretical foundation, on the other hand, is something first contemplated: from θεορος, from what we spectate (we touch not), and those speculations — those speculative fictions — become our foundation. When we meet the author in the work, we meet the subject matter of the daily weather of the author’s mind: his fabricated memory of a new experience. This sets us up for actualizing his hypotheses. The poetry of Kvothe leads to the science of Chronicler, the man who has come to vivisect the legend of innkeeper Kote’s former life as Kvothe. The secondary faith of Tolkien (Middle Earth) predicated on the primary faith of Tolkien (in his case, Catholicism) itself predicates the doubly faithless naturalistic journalism of Marquez (absurdity that follows demythologizing). For Being — total Being — cannot be destroyed or created, only donated.

First MacDonald:

It is the far-seeing imagination which beholds what might be a form of things, and says to the intellect: “Try whether that may not be the form of these things;” which beholds or invents a harmonious relation of parts and operations, and sends the intellect to find out whether that be not the harmonious relation of them—that is, the law of the phenomenon it contemplates. Nay, the poetic relations themselves in the phenomenon may suggest to the imagination the law that rules its scientific life. Yea, more than this: we dare to claim for the true, childlike, humble imagination, such an inward oneness with the laws of the universe that it possesses in itself an insight into the very nature of things.

…It is the imagination that suggests in what direction to make the new inquiry–which, should it cast no immediate light on the answer sought, can yet hardly fail to be a step towards final discovery. Every experiment has its origin in hypothesis; without the scaffolding of hypothesis, the house of science could never arise. And the construction of any hypothesis whatever is the work of the imagination. The man who cannot invent will never discover. The imagination often gets a glimpse of the law itself long before it is or can be ascertained to be a law.

… Coleridge says that no one but a poet will make any further great discoveries in mathematics; and Bacon says that “wonder,” that faculty of the mind especially attendant on the child-like imagination, “is the seed of knowledge.” The influence of the poetic upon the scientific imagination is, for instance, especially present in the construction of an invisible whole from the hints afforded by a visible part; where the needs of the part, its uselessness, its broken relations, are the only guides to a multiplex harmony, completeness, and end, which is the whole. From a little bone, worn with ages of death, older than the man can think, his scientific imagination dashed with the poetic, calls up the form, size, habits, periods, belonging to an animal never beheld by human eyes, even to the mingling contrasts of scales and wings, of feathers and hair. Through the combined lenses of science and imagination, we look back into ancient times, so dreadful in their incompleteness, that it may well have been the task of seraphic faith, as well as of cherubic imagination, to behold in the wallowing monstrosities of the terror-teeming earth, the prospective, quiet, age-long labour of God preparing the world with all its humble, graceful service for his unborn Man. The imagination of the poet, on the other hand, dashed with the imagination of the man of science, revealed to Goethe the prophecy of the flower in the leaf. No other than an artistic imagination, however, fulfilled of science, could have attained to the discovery of the fact that the leaf is the imperfect flower.

[George MacDonald, “The Imagination: It’s Function and Culture,” The Golden Key, accessed September 5, 2021, http://www.george-macdonald.com//etexts//etexts/the_imagination.html.]

Later in Paxon (108-111):

The hypothesis that perception is independent of and prior to representation is precluded in phenomenological inquiry. Although Husserl set out to demonstrate the distinction between perception (or, as he called it, “retention”) and representation, his phenomenological enterprise revealed — according to Derrida and the whole deconstructive appropriation of phenomenology — that perception itself is structured like a language. “Perception is always already representation” (Norris, Practice, 48). Prosopopeia, even as a perceptual and putatively unconscious, “pre-tropological,” or pre-linguistic phenomenon, is always-already a proposition: everything in the unconscious mind can be described in terms of a mutual system of tropes or figures.) Seeing faces in the clouds constitutes a poetic or textual act even though the experience may seem virtual and unmediated.

In other words we have the objective within the subjective that the subject sees and the subjective within the objective that the objective transmits. But there’s also sort of a tertium quid, the fandom of both that is always already both and neither as a third thing. Said again, the personification contains reification within it (for how may an inanimate object receive the animating breath of life if not first being inanimate?) and reification contains personification within it (for how may Frosty the Snowman return to an inanimate face drawn in the snow if not having first been personified as such?) and therefore the always-already third thing of the mediating mind of the reader? Of disembodied voices and asides spoken to inanimate objects that end, ultimately, in the selling of ephemera at events like Comic Con?

Paxon goes on to point to Bussy D’Ambois where George Chapman compares the act of charming a deceptive mask for the creature Sin, a figure, to the primal experience of perceiving faces in clouds or chunks of cartilage that Policy robes in her own cloth and makes into a real systemic monster. So is the face of Sin real or not?

It depends.

In The Name of the Wind, we watch this exact spectrum of Paxon’s Greimas Square of Personifcation / Reification ; Dialog / Apostrophe play out in the character of Kvothe. When we meet Kvothe (a name the text tells us means “to know” but sounds like “quothe” as in speech, the word derived from saying and convoking and knowing and writing — all from the resin of the sorts of trees under which Albert made laws and Baldyr stole lightning and others made ink), he goes by the name Kote. Like a coat or perhaps a cote, a shelter for pigeons and small animals. And he’s silent and waiting to die, much like the abstraction at the end of the Divine Comedy, the divine silence. The Error of Spencer. Death in Chaucer.

A Chronicler — a scribe — much like Spenser’s Eumnestes in Queene shows up wanting to get the true record on Kvothe’s life, which has grown to mythic proportions. Both the oral tradition of Kvothe and the manuscripts of Chronicler suffer decay, in various ways, but the economy of story starts with the telling and ends with the writing and eventually decaying until silence resumes and stories begin again.

So Kvothe starts to tell the story of whether or not he really burned down the city of Trebon and whether or not he fought a dragon and the rest of the myths that surround his reputation. As Kote — the empty coat or the mere abandoned shed for pigeon crap — tells the story, he begins to come alive as the Know-er. In his room sits a locked box either containing his true name or his death or a passage leading to the Land of Personification, but he’s surrounded by other elements of personification and reification. Folly, the sword, hangs on the wall for the reification of the folly of a willful pride and the things men do for love (perhaps even a reification of his love, though we can’t be sure until book three comes out). Bast — apparently the bastard child of some fairy king, perhaps Kvothe himself — helps him clean his mugs.

The personification of to know, to story is Kvothe in the mimetic level of story. The empty coat (or cote; or, worse, the German imperative for defecate) Kote tells the story with Chronicler on the diegetic level. Their dialog seems to show a true human representation.

But you also have mute humans within the level of story that ought to speak, even mute doors, mute texts, inaccessible archives. Fae creatures show up in the diegetic level, but personifications show up as well.

Rothfuss practices “J.G. Frazer’s quaint terminological division between ‘homeopathic magic’ and ‘contagious magic’” in the story — naming and sympathy. Like Will in Piers Plowman, Kvothe exercises at the very start of the story the narratorial power of naming brand new characters on the spot and that capacity to name shifts with his narrative control, when he’s near death (perhaps Kote is a man “waiting to die” in order to be able to change his own name back to Kvothe, perhaps because he can only tell stories when Kote dies so that Kvothe — the personification and auctophany — may be born, perhaps because he can never die now that he’s made the bargain he’s made on the story level and the story has affected real life). At the center of the personification narrative lies those names the narrator endows on figures, how he endows, when he endows them.

This even includes several of his own “In the beginning…” moments.

As Will in Plowman delights in the privileged foreknowledge of story events (naming forms his initial problem of narration, he identifies on sight personification figures, he spans diegetic registers), so too does Kote delight in such knowledge and his auctophany personifies that narrative foreknowledge. Yet, just as with Will, Kvothe occasionally forgets his role depending on the characters he meets such as Cthaeh (and vice versa with the Cthaeh — normally an all-timeline-knowing, all-space-knowing demon who suddenly can’t see Kvothe’s future) — Thought, Imagination, Anima, Faith, and Spes — every personification Will meets face to face initially, he knows not. In Will’s case, the narratorial epistemology shows a contradiction: at times, Will has omniscience and at others he’s comically obtuse. Similarly with Kvothe. How does this work?

On the diegetic level of the outer dream, Will has the power to name on sight only those he observes with narrative distance such as in a tableau or iconographic portrait. So too can Kote (the narrator) name Folly, the sword (perhaps a reified version of his love Denna, perhaps an embodiment of the moon, whom he chases, perhaps the distillation of the name of all iron swords) or other personifications that other characters mention. He cannot, and Will cannot, identify personifications he meets for the first time, face-to-face.

On the metadiegetic level of the inner dream, Will holds sway over naming on sight both those met at a distance and those met face to face. In a similar way, Kvothe (the character) gets the names right across the board.

Through narratology proper, foregrounding both #1 and #2 as possibilities for the ideal author, it foregrounds total narratorial omnisciences — extradiegesis. Narrating the story by a narrator exclusively outside. Homodiegetic calls up images of mortal narrator, extradiegetic calls up images of godlike narrator. Indeed, Kote (like Will in the mystical trance state) summons up godlike powers while Kvothe gets hurt. Often.

“This calls up the fourth potential epistemological variation: the world and its entire narrative is a book penned by God according to Hugh of St. Victor. Through the person of Jesus, God the Transcendent father enters his own narrative text.” God transcendent, extradiegetic and even heterodiegetic enters and becomes homodiegetic: even mimetic in infancy. Kote, so far, has not done this. But this would be auctophany. In Will’s case, he has transforming — even Neoplatonic — dreams where he’s “lifted” in to transcendent, metaphysical realms. Dante pulls on this as well. The inner dream, then, penetrates the penetration — moving from Holy Place into Holy of Holies — metamorphizing Will’s knowledge into, to borrow an alchemical process, a sublimated, distilled, and coagulated quality. “His ability to recognize and name all personified characters on the spot reveals that he had penetrated into, or moved up to, a cosmic order that is as ontologically different from the outer dream level of diegetic narrative as the outer dream level is from the level of the mimetic frame, waking reality.” [James J. Paxson, The Poetics of Personification (Cambridge University Press, 1994) 126-131.]

Therefore Will’s third-person knowledge can be remembered in his first-person narration at times: certainly he sees everyone and everything as “personified essence.” Certainly King, the character in Stephen King’s novels, forgets often. Can Kote’s third-person knowledge be remembered in Kvothe’s first-person narration?

We don’t quite know for sure (book three of the trilogy does not yet exist so per Augustine, we do not yet have the “organic unity” of the significance of Rothfuss’s entire literary project that makes the pilgrim Kvothe himself metamorphosed into the poet Kote “capable at last of telling the story we have heard”), but we have hints. They both, Will and Kote, enjoy more knowledge on “heterodiegetic” narration and less with “homodiegetic” narration, third person verses first person respectively. The closer Will gets physically to the personification figures, the less he knows. For Kvothe, it’s the opposite as third person is the diegetic level, but the epistemological variation remains. And as Kvothe the character in the story becomes Kote the storyteller in the Waystone Inn (perhaps even a storyteller stuck in a waystone, if the stone door and “waiting to die” offers any indication), a transition happens much like putting a face on a cloud that eventually rains and makes still another face in the pond. In Kvothe’s case, the face is hideous: half-Chandrian, half-psychopathic murderer.

So which is it?

Was the face there to begin with or did we make it?

García Márquez assumes along with the naturalists that we project faces onto the world, but the truth is the opposite: perception’s structured like language. We see faces because faces exist in the world, always already representation, a pre-tropological, pre-linguistic phenomenon. We see tropes because the world is tropes. We see faces in the cloud because personification is structured into the fabric of clouds. You can tell people that elephants flew overhead and unless they want to willfully disbelieve, they will say with childlike faith, “What happened next?” What better way, then, to completely change society for the better than to rewrite, revise, and collaborate in reinventing the tropes, figures, and narratives we tell ourselves? It’s no accident that the great scientific breakthroughs of history started not in the lab, but in the myth and legend and science fiction section of the library. Martin says we write it to “find the colors again,” again drawing the connection to dreams.

“What can any of them know about her?” — coming from the man whose name means to Know. “What can any of them know about me?”

Chronicler swallowed against the dryness in his throat. “Only what they’re told.”

Rothfuss, Patrick. The Name of the Wind (The Kingkiller Chronicle Book 1) (p. 47). Astra Publishing House. Kindle Edition.

This post is a condensed, revised version of the chapter 6 portion of The Name of the Wind reread on my site, which will make little sense if you haven’t read the book. Once you have, perhaps start with the prologue.