Is Murakami a one trick pony? A dialog on writers. As ponies. Turning tricks.

A dialog about a circulating Substack note.

I texted Kendall a note circulating on Substack by and quoting a professor who accused Murakami of being a one trick pony. I texted him for two reasons: one, Kendall loves Murakami and I haven’t read a single paragraph of the author; two, to troll Kendall into his first post here. It’s a dialog and it’s about the author, authors, and whether we ever have more than one trick.

— You see these?

— I don’t know, this guy seems pretty familiar with Japanese literature, which is what makes this take a bit baffling to me.

Lancelot Schaubert — Hahahaha. Why?

Kendall Bates — They’re all kinda like that, in a sense.

Lancelot Schaubert — Every one?

Kendall Bates — Yes and no. The more Japanese literature you read, the more apparent it is that Murakami didn’t emerge from a vacuum (or cobble himself together from Vonnegut’s spare parts). The field is full of Murakami-isms, or more appropriately, vice versa.

To be fair, I know the “one trick” that he’s talking about… and it’s a roughly fair assessment. But that one trick is just a single element of his books—a common thread, and you either like it or you don’t. Find me an author for whom that isn’t true. Rowling is a one trick pony. Lewis is a one trick pony. Gaiman, Sanderson—even Tolkien and Chesterton, to a certain degree.

Lancelot Schaubert — Look, table Rowling’s politics and everything connected to it, she’s not a one trick pony. Have you read read her other work? The Galbraith stuff? Casual Vacancy?

Kendall Bates — Yeah, I’ve read and have loved some of the Galbraith stuff.

Lancelot Schaubert — I immediately retract my assumption in shame: alas, I will diminish, and go into the east, and remain a broken Lancelot.

Lewis? Arguably one trick, though his short stories show potential of other stuff.

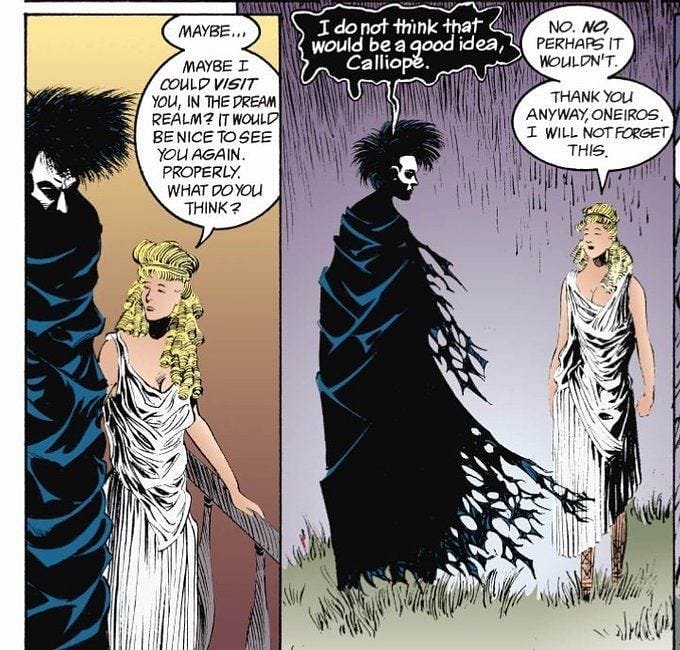

Gaiman, yes. Gaiman absolutely yes and it’s what drives me nuts about his (as we now know) worst character traits:

Neil Gaiman's Prostitutes

Neil Gaiman’s writing often features the allegedly radical free sexuality of temple prostitutes in ancient Greece and Babylon. I wonder if Gaiman’s underlying ideology is the third rail of shock electrifying recent exposes regarding his character. For those unaware, “

Sanderson, no — not after the release of the secret projects and his YA stuff, comics, TTRPG, etc. At least… I’m wondering what you mean at this point.

Tolkien… depends on if the posthumous stuff counts, the translations, etc.?

Chesterton? Certainly on the koans, but honesty he’s one of the more diverse writers of his time. He wrote about freaking anything and in any medium. Even in his anti-semitic stereotypes — and they are there and they are awful — he was almost alone in his era condemning eugenics clearly, loudly, and rationally. It’s rather remarkable to me that conservatives hold him up so often, given, say, distributism (hello there, Pope Leo XIII) or French democracy or his tremendous appetite for no tyrant or king in any form except some poetic romantic bloodlust for the past or as a point to fully illustrate the beauty of democracy.

Kendall Bates — Look, I didn’t include a single author in that list that I don’t also love. Rowling’s stories are all mysteries centering around characters on the fringes. Lewis barely wrote a thing that wasn’t a (wonderful) Christo-Socratic inversion of his favorite classical works. Sanderson can’t seem to write a book without reinventing alchemy. Gaiman is always Gaiman—for better and worse. And Tolkien is always Tolkien—for better and best.

All of this is just to say they’re all iterating on their own writing agenda. They’re memorable because of it, not in spite of it. We just don’t mind because we happen to find their “one trick” compelling.

Lancelot Schaubert — I mean that’s true, though I do wonder if The Casual Vacancy fits your Rowling schema, I can concede that certainly. That common thread is “them.” I was more curious as to your reaction than I was agreeing with the guy, for the record. I’ve read nothing by Murakami, so I was saying, “Hey, my friend the bear, this guy wants to poke ya.”

Kendall Bates — Yeah, I mean, all of this is exactly to my point. The criticism of Murakami is identical. There’s something common in all of his works—a voice, a character type, a palette of themes/interests—just like there’s something common in all of the works of the rest. Whether that amounts to them being a “one trick pony” I think says more about the plaintiff than the defendant.

If the critique is about the “magical realism” (I hate that term), he could just as readily take aim at Yukio Mishima, Kobo Abe, and plenty of contemporary authors who’ve dabbled in the dream logic. If it’s about its ubiquity, novel after novel, I’d ask if he’s read South of the Border…, After Dark, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki…, and plenty of his short stories with minimal magic. (I’m of course taking for granted he’s already read Norwegian Wood.)

If he wants to criticize the disaffected and alienated, borderline despondent main character, read any of the other boku-novels—that’s kind of the whole premise of the genre. Read Osamu Dazai for the most miserable example of this (No Longer Human is largely auto-biographical—and that’s not at all to the man’s credit). Natsume Soseki is perhaps my favorite Japanese author and one of the great precursors to the genre. Mieko Kawakami is also fantastic—she doesn’t quite write boku-novels, but something like an inversion of them. Still first-personal and alienated, but more philosophically sharp than detached. Still disaffected, just different. Plenty of other examples here.

There are certainly other things to criticize in Murakami—the pixie-ish women replete in his novels (though somewhat less so in his short stories), the fixation on depictions of really weird sex (though better “weird” than “sexy”, if you ask me), etc. Some (fewer these days) have seen fit to criticize how “Western” they feel (eating McDonald’s, listening to Bob Dylan, drinking beer and whiskey by the liter, endless references to jazz records), to which I can only say: welcome to contemporary Japan—Meiji ended over a hundred years ago.

Lancelot Schaubert — Haha. I’m thinking now of the proliferation of American wedding chapels: all the vestments of sacrament without any clue as to what any of it means.

Kendall Bates — The long and short of it is: all of Murakami’s apparent vices long precede him. The only thing Murakami pioneered is Murakami himself. It’s jazz—he is the music here, not the chords or modes. You either get it or you don’t and that’s cool either way. Personally, I think it’d be dope to drink highballs in a bar, watching baseball and arguing with a cat about psychological continuity between innings. I’d probably read a thousand scenes like that.

Lancelot Schaubert — Why do you hate the term “magical realism?”

Kendall Bates — I could give you the annoying answer—something like, “Because it denies the magical in the real, and the real in the magical,” or whatever. But the truth of it probably is that it just sounds dumber than surrealism.

And besides, I think surrealism fits the bill better. I mean, the “magic” in these stories is always a rupture in logic, not a backdrop. It’s not as though the story treats it as a matter of common, everyday occurrence. The magic isn’t so much in the world as it is in the situation. Now the characters may react as if it were—they may treat it with more or less indifference—but that’s more a function of the characters themselves (see above).

Lancelot Schaubert — It reminds me of that “magical realism” book The Rules of Magic. In which there are no rules, no real magic, and the magical realism is all the surrealism of… certainly an odd perspective on trauma.

What do you make of the claim that Murakami is an embarrassment in Japan, especially considering it as an honor/shame culture?

I mean, you married Japanese and just got back to the states from Japan, so you’re basically turning Japanese… (saying that advisedly as someone whose close cousin has been stationed there functionally permanently for ages and many of his closer high school and college buddies have been there for a decade and a half….)

Kendall Bates — Murakami is absolutely not seen as an “embarrassment” in Japan. At worst he’s considered a bit of an outsider, because he doesn’t write classically “Japanese” novels—his prose is famously jarring and bizarre in Japanese, which doesn’t really come through in translation. This is by design, by the way. He developed his voice by writing in his own stilted English and then translating back into Japanese, creating something almost choppy and too direct for a language that thrives on implication. (Imagine Cormac McCarthy didn’t speak English).

But even that reputation—of being too “Western” or whatever—is decades removed from the present. At this point he’s an institution in his own right. And the same thing happened with our own postmoderns, right? Literary weirdos with a cult following—too ironic, too unstructured, all style and not enough substance for the old heads. Now they’re required reading.

Lancelot Schaubert — Returning to magical realism for a moment, what do you think of Wordsworth and Coleridge’s project? How does it compare with the inherent cynicism of much of magical realism?

Kendall Bates — Unfortunately, my volume of Coleridge sits unread on my shelf. Did you have any thoughts?

Lancelot Schaubert — Only half baked thoughts. It seems to me their project involved the reenchantment of nature (Wordsworth) and the secondary faith — or as Coleridge said in a lesser form, the “suspension of disbelief” — in a secondary world, which requires an attention to detail. It seems to me that magical realism often these days occupies a this-world space that does not reentrant, but affirms a disenchantment, and scoffs in the general direction of secondary worlds as a whole.

This seems to me to be some combination of simply the last gasps of modernism as it tries to affirm through fantastic exemplars that enchantment is gone. For instance, a stone golem saying “Gott ist tot” or whatever. It could also be a blend with post-modernism of deconstructing the idea of the narrative itself. Neither of which, to me, seem appealing. On the one hand, we do need the many and social constructs do exist. On the other, so do metanarratives and we have to start affirming truth at some point, otherwise we’re reduced to mumbling insanities in the corner.

Neither of these (an abyss of empathy, an abyss of truth) seem very compelling to me, particularly since I absolutely believe that all fiction is speculative philosophy and all speculative philosophy is fantasy

Kendall Bates — You could be right about that. I don’t claim exhaustive familiarity with the genre as a whole, so I don’t want to speak out of turn—but regarding Murakami specifically, I think this is at least somewhat right. I wouldn’t say the narrative is totally deconstructed—most of his novels still follow the contours of a hero’s journey, however loosely. Nor would I necessarily diagnose an abyss of empathy or truth. But you’re right that the magic is almost never enchanting.

In Gaiman, say, it’s almost always some hidden world—a mystery the protagonist is being let in on. It’s an initiation or a baptism. In Murakami, the magic is something he’s subjected to—a symptom of something already there. It’s an estrangement made visible and concrete. But both, in their own way, are using it to get their protagonists back to the same place. Back to the world and back to themselves.

Think of it as Gaiman’s threshold versus Murakami’s mirror.

Lancelot Schaubert — I suppose that’s the real trouble here: that folks see escape as delusion and are using stories like this to affirm delusions as opposed to encouraging speculative philosophy that draws us deeper into the world itself: to friends, to trees, to fields, to our children, to the wind moreso than any dehumanizing machinery.

These critical types use “escape” as a derisive term (I don’t mean to imply the fiction writers do this, though Gaiman certainly derides speculative philosophy in his escapism, the one thing his work desperately needs, ironically enough), but the funny thing is, the one person who actually wrote a thorough analysis of the philosophy of “escapism” not only believed in escapist literature and practiced it, but saw its purpose as healthy and helpful to the real world — this a WWI veteran who helped with code cracking in WWII as much as his next door neighbors. I’ll give him the last word and his name is Tolkien:

I will now conclude by considering Escape and Consolation, which are naturally closely connected. Though fairy-stories are of course by no means the only medium of Escape, they are today one of the most obvious and (to some) outrageous forms of “escapist” literature; and it is thus reasonable to attach to a consideration of them some considerations of this term “escape” in criticism generally.

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds.

Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks andtalks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter. Just so a Party-spokesman might have labelled departure from the misery of the Führer's or any other Reich and even criticism of it as treachery. In the same way these critics, to make confusion worse, and so to bring into contempt their opponents, stick their label of scorn not only on to Desertion, but on to real Escape, and what are often its companions, Disgust, Anger, Condemnation, and Revolt. Not only do they confound the escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter; but they would seem to prefer the acquiescence of the “quisling” to the resistance of the patriot. To such thinking you have only to say “the land you loved is doomed” to excuse any treachery, indeed to glorify it.

For a trifling instance: not to mention (indeed not to parade) electric street-lamps of mass-produced pattern in your tale is Escape (in that sense). But it may, almost certainly does, proceed from a considered disgust for so typical a product of the Robot Age, that combines elaboration and ingenuity of means with ugliness, and (often) with inferiority of result. These lamps may be excluded from the tale simply because they are bad lamps; and it is possible that one of the lessons to be learnt from the story is the realization of this fact.

But out comes the big stick: “Electric lamps have come to stay,” they say. Long ago Chesterton truly remarked that, as soon as he heard that anything “had come to stay,” he knew that it would be very soon replaced—indeed regarded as pitiably obsolete and shabby. “The march of Science, its tempo quickened by the needs of war, goes inexorably on ... making some things obsolete, and foreshadowing new developments in the utilization of electricity”: an advertisement. This says the same thing only more menacingly. The electric street-lamp may indeed be ignored, simply because it is so insignificant and transient. Fairy-stories, at any rate, have many more permanent and fundamental things to talk about. Lightning, for example. The escapist is not so subservient to the whims of evanescent fashion as these opponents. He does not make things (which it may be quite rational to regard as bad) his masters or his gods by worshipping them as inevitable, even “inexorable.” And his opponents, so easily contemptuous, have no guarantee that he will stop there: he might rouse men to pull down the street-lamps. Escapism has another and even wickeder face: Reaction.

Not long ago—incredible though it may seem—I heard a clerk of Oxenford declare that he “welcomed” the proximity of mass-production robot factories, and the roar of self-obstructive mechanical traffic, because it brought his university into “contact with real life.” He may have meant that the way men were living and working in the twentieth century was increasing in barbarity at an alarming rate, and that the loud demonstration of this in the streets of Oxford might serve as a warning that it is not possible to preserve for long an oasis of sanity in a desert of unreason by mere fences, without actual offensive action (practical and intellectual). I fear he did not.

In any case the expression “real life” in this context seems to fall short of academic standards. The notion that motor-cars are more “alive” than, say, centaurs or dragons is curious; that they are more “real” than, say, horses is pathetically absurd. How real, how startlingly alive is a factory chimney compared with an elm-tree: poor obsolete thing, insubstantial dream of an escapist!

For my part, I cannot convince myself that the roof of Bletchley station is more “real” than the clouds. And as an artefact I find it less inspiring than the legendary dome of heaven. The bridge to platform 4 is to me less interesting than Bifröst guarded by Heimdall with the Gjallarhorn. From the wildness of my heart I cannot exclude the question whether railway-engineers, if they had been brought up on more fantasy, might not have done better with all their abundant means than they commonly do. Fairy-stories might be, I guess, better Masters of Arts than the academic person I have referred to.

Much that he (I must suppose) and others (certainly) would call “serious” literature is no more than play under a glass roof by the side of a municipal swimming-bath. Fairy-stories may invent monsters that fly the air or dwell in the deep, but at least they do not try to escape from heaven or the sea.

And if we leave aside for a moment “fantasy,” I do not think that the reader or the maker of fairy-stories need even be ashamed of the “escape” of archaism: of preferring not dragons but horses, castles, sailing-ships, bows and arrows; not only elves, but knights and kings and priests.

For it is after all possible for a rational man, after reflection (quite unconnected with fairy-story or romance), to arrive at the condemnation, implicit at least in the mere silence of “escapist” literature, of progressive things like factories, or the machine-guns and bombs that appear to be their most natural and inevitable, dare we say “inexorable,” products.

“The rawness and ugliness of modern European life”—that real life whose contact we should welcome —“is the sign of a biological inferiority, of an insufficient or false reaction to environment.” The maddest castle that ever came out of a giant's bag in a wild Gaelic story is not only much less ugly than a robot-factory, it is also (to use a very modern phrase) “in a very real sense” a great deal more real. Why should we not escape from or condemn the “grim Assyrian” absurdity of top-hats, or the Morlockian horror of factories? They are condemned even by the writers of that most escapist form of all literature, stories of Science fiction. These prophets often foretell (and many seem to yearn for) a world like one big glass-roofed railway-station. But from them it is as a rule very hard to gather what men in such a world-town will do.

They may abandon the “full Victorian panoply” for loose garments (with zip-fasteners), but will use this freedom mainly, it would appear, in order to play with mechanical toys in the soon-cloying game of moving at high speed. To judge by some of these tales they will still be aslustful, vengeful, and greedy as ever; and the ideals of their idealists hardly reach farther than the splendid notion of building more towns of the same sort on other planets. It is indeed an age of “improved means to deteriorated ends.” It is part of the essential malady of such days—producing the desire to escape, not indeed from life, but from our present time and self-made misery— that we are acutely conscious both of the ugliness of our works, and of their evil. So that to us evil and ugliness seem indissolubly allied. We find it difficult to conceive of evil and beauty together. The fear of the beautiful fay that ran through the elder ages almost eludes our grasp. Even more alarming: goodness is itself bereft of its proper beauty. In Faerie one can indeed conceive of an ogre who possesses a castle hideous as a nightmare (for the evil of the ogre wills it so), but one cannot conceive of a house built with a good purpose—an inn, a hostel for travellers, the hall of a virtuous and noble king—that is yet sickeningly ugly. At the present day it would be rash to hope to see one that was not—unless it was built before our time.

This, however, is the modern and special (or accidental) “escapist” aspect of fairy-stories, which they share with romances, and other stories out of or about the past. Many stories out of the past have only become “escapist” in their appeal through surviving from a time when men were as a rule delighted with the work of their hands into our time, when many men feel disgust with man-made things.

But there are also other and more profound “escapisms” that have always appeared in fairy-tale and legend. There are other things more grim and terrible to fly from than the noise, stench, ruthlessness, and extravagance of the internal-combustion engine. There are hunger, thirst, poverty, pain, sorrow, injustice, death. And even when men are not facing hard things such as these, there are ancient limitations from which fairy-stories offer a sort of escape, and old ambitions and desires (touching the very roots of fantasy) to which they offer a kind of satisfaction and consolation. Some are pardonable weaknesses or curiosities: such as the desire to visit, free as a fish, the deep sea; or the longing for the noiseless, gracious, economical flight of a bird, that longing which the aeroplane cheats, except in rare moments, seen high and by wind and distance noiseless, turning in the sun: that is, precisely when imagined and not used.

There are profounder wishes: such as the desire to converse with other living things. On this desire, as ancient as the Fall, is largely founded the talking of beasts and creatures in fairy-tales, and especially the magical understanding of their proper speech. This is the root, and not the “confusion” attributed to the minds of men of the unrecorded past, an alleged “absence of the sense of separation of ourselves from beasts.” A vivid sense of that separation is very ancient; but also a sense that it was a severance: a strange fate and a guilt lies on us. Other creatures are like other realms with which Man has broken off relations, and sees now only from the outside at a distance, being at war with them, or on the terms of an uneasy armistice. There are a few men who are privileged to travel abroad a little; others must be content with travellers' tales. Even about frogs. In speaking of that rather odd but widespread fairy-story The Frog-KingMax Müller asked in his prim way: “How came such a story ever to be invented? Human beings were, we may hope, at all times sufficiently enlightened to know that a marriage between a frog and the daughter of a queen was absurd.” Indeed we may hope so! For if not, there would be no point in this story at all, depending as it does essentially on the sense of the absurdity.

Folk-lore origins (or guesses about them) are here quite beside the point. It is of little avail to consider totemism. For certainly, whatever customs or beliefs about frogs and wells lie behind this story, the frog-shape was and is preserved in the fairy-story precisely because it was so queer and the marriage absurd, indeed abominable. Though, of course, in the versions which concern us, Gaelic, German, English, there is in fact no wedding between a princess and a frog: the frog was an enchanted prince. And the point of the story lies not in thinking frogs possible mates, but in the necessity of keeping promises (even those with intolerable consequences) that, together with observing prohibitions, runs through all Fairyland. This is one of the notes of the horns of Elfland, and not a dim note.

And lastly there is the oldest and deepest desire, the Great Escape: the Escape from Death.

Fairy-stories provide many examples and modes of this—which might be called the genuine escapist, or (I would say) fugitive spirit. But so do other stories (notably those of scientific inspiration), and so do other studies. Fairy-stories are made by men not by fairies. The Human-stories of the elves are doubtless full of the Escape from Deathlessness. But our stories cannot be expected always to rise above our common level. They often do. Few lessons are taught more clearly in them than the burden of that kind of immortality, or rather endless serial living, to which the “fugitive” would fly. For the fairy-story is specially apt to teach such things, of old and still today. Death is the theme that most inspired George MacDonald.

Remember this - in the 1920's a Japanese Haiku master was invited to the United States for a tour to explain the subtleties of writing Haiku. But, not familiar with the "subtleties" of American thought, he carelessly said "Once you have learned the rules - there are no rules." And like Charles Shultz's Snoopy, Americans hear "Wah waa wuh waa.. there are no rules." So, unless we are reading a Japanese author's work in Japanese, it may be the translation that's lacking in substance.

Hey thanks for the shout out! I'm shocked how much that little note blew up. For some context this was something that a professor said to me back in ~2006. It might have resonated with me so strongly because I was just an impressionable 20 year old at the time 😂