Los Angeles Fires — a History of Angels Braving Flames Mythologies

A brief history of my disaster experiences, myths of κατάβασις, and paradises built in hell — all in the shadow of the fires overtaking Los Angeles and Hollywood.

So far, all of my check-ins for Los Angeles sound at least physically safe — if you aren’t and you’re reading this, my comfort for your loss. If you lost your home, also my comfort for your loss. Let us know in the comments how this community can help and for everyone else, I added a category on the donation page for those who want to send money to artists directly affected by the California fires. Just select “California fires” in the drop down arrow and I’ll forward it all on to our partner org who has been on the ground for decades. If you’d prefer, there’s also the Pasadena Educational Foundation, which supports the public schools. If you’re reading this and in an evacuation zone and haven’t left, please heed CalFire and get out.

As of right now, there are so, so many in our network who have evacuated Hollywood. In our network as of right now, we know of a fine artist, a composer, a film director, an actor, a teacher who have all lost homes. Then there are the more famous colleagues whom you likely have already heard about on social media.

This included checking in on our uncles and aunts during the recent Tampa hurricane. This time, however, it’s a surrogate aunt, our partners in Hollywood, and several close friends and colleagues. A prospectus I sent to an estate’s literary agent only last night was forwarded to a producer who I realized, after checking his Patreon, had also evacuated and will be offline for the foreseeable future — my anecdote should serve as an example, if nothing else, for one of our many meaninglessly mild inconveniences I’ll address in moment.

That said: if you’re directly affected and any part of this piece feels too much to read, please wait until later — be self-discerning with what will and won’t help you as you navigate this or any other disaster, for there’s a chance this will get shared again in the future. But I did want to talk today a little about our own personal experiences as well as about the various myths — and historical instances — of literal and figurative paradises built in hell, of recovery efforts, of myths where Hell itself was harrowed and hanging gardens were grown anew.

But these moments drum wildly mixed feelings deep within me like the time the entirety of 15th street in Joplin was gone, wiped out alongside the equivalent of the net worth of J.K. Rowling so many neighbors gone in tragic ways. If this happened to you, again, my comfort for your loss. It brings to mind the policeman who, merely directing traffic one week after the storm had passed, was struck by lightning and killed after skin grafts failed in Springfield. After the tornado passed through, he was the tallest thing on that hill and standing tall was the death of him in the second storm.

What do you feel?

These moments also throw other eels into my inner rain barrel full of emotional eels, churning up Chesterton’s phrase I quote often. The phrase doesn’t necessarily apply to those who have directly suffered great loss, but first rather to those of us on the periphery of the disaster — those who have been merely inconvenienced, but grumble as loud or perhaps even louder as those who have truly suffered. His phrase says that an inconvenience, rightly considered, is an adventure and an adventure wrongly considered is an inconvenience.1 (To make it abundantly clear, this current piece intends to engender empathy and hopeful vision, not grumbling).

In this situation, his phrase could include water rationing, power outages well outside the evacuation zone that aren’t life threatening (they are for a surgical ward, they are not for your video game), delays in email, or your local fire department volunteering to bring aid to California. It could include school cancellations, or administrative backlog. The list goes on.

Chesterton originally applied his phrase to the flooding of his hometown which, with minimal damage, for the well-ordered mind became a kind of adventure upon an archipelago. And the meditation is helpful for those of us who complain or fight over something trite today, though we have not died, been burned, become separated from our families, or lost a home to this blaze. It’s a great meditation for those of us today who are merely inconvenienced:

I feel an almost savage envy on hearing that London has been flooded in my absence, while I am in the mere country. My own Battersea has been, I understand, particularly favoured as a meeting of the waters. Battersea was already, as I need hardly say, the most beautiful of human localities. Now that it has the additional splendour of great sheets of water, there must be something quite incomparable in the landscape (or waterscape) of my own romantic town. Battersea must be a vision of Venice. The boat that brought the meat from the butcher’s must have shot along those lanes of rippling silver with the strange smoothness of the gondola. The greengrocer who brought cabbages to the corner of the Latchmere Road must have leant upon the oar with the unearthly grace of the gondolier. There is nothing so perfectly poetical as an island; and when a district is flooded it becomes an archipelago.

Some consider such romantic views of flood or fire slightly lacking in reality. But really this romantic view of such inconveniences is quite as practical as the other. The true optimist who sees in such things an opportunity for enjoyment is quite as logical and much more sensible than the ordinary “Indignant Ratepayer” who sees in them an opportunity for grumbling. Real pain, as in the case of being burnt at Smithfield or having a toothache, is a positive thing; it can be supported, but scarcely enjoyed.

But, after all, our toothaches are the exception, and as for being burnt at Smithfield, it only happens to us at the very longest intervals. And most of the inconveniences that make men swear or women cry are really sentimental or imaginative inconveniences–things altogether of the mind. For instance, we often hear grown-up people complaining of having to hang about a railway station and wait for a train. Did you ever hear a small boy complain of having to hang about a railway station and wait for a train? No; for to him to be inside a railway station is to be inside a cavern of wonder and a palace of poetical pleasures. Because to him the red light and the green light on the signal are like a new sun and a new moon. Because to him when the wooden arm of the signal falls down suddenly, it is as if a great king had thrown down his staff as a signal and started a shrieking tournament of trains. I myself am of little boys’ habit in this matter. They also serve who only stand and wait for the two fifteen. Their meditations may be full of rich and fruitful things. Many of the most purple hours of my life have been passed at Clapham Junction, which is now, I suppose, under water. I have been there in many moods so fixed and mystical that the water might well have come up to my waist before I noticed it particularly. But in the case of all such annoyances, as I have said, everything depends upon the emotional point of view. You can safely apply the test to almost every one of the things that are currently talked of as the typical nuisance of daily life.

Now a man could, if he felt rightly in the matter, run after his hat with the manliest ardour and the most sacred joy. He might regard himself as a jolly huntsman pursuing a wild animal, for certainly no animal could be wilder. In fact, I am inclined to believe that hat-hunting on windy days will be the sport of the upper classes in the future. There will be a meet of ladies and gentlemen on some high ground on a gusty morning. They will be told that the professional attendants have started a hat in such-and-such a thicket, or whatever be the technical term. Notice that this employment will in the fullest degree combine sport with humanitarianism. The hunters would feel that they were not inflicting pain. Nay, they would feel that they were inflicting pleasure, rich, almost riotous pleasure, upon the people who were looking on. When last I saw an old gentleman running after his hat in Hyde Park, I told him that a heart so benevolent as his ought to be filled with peace and thanks at the thought of how much unaffected pleasure his every gesture and bodily attitude were at that moment giving to the crowd.

The same principle can be applied to every other typical domestic worry. A gentleman trying to get a fly out of the milk or a piece of cork out of his glass of wine often imagines himself to be irritated. Let him think for a moment of the patience of anglers sitting by dark pools, and let his soul be immediately irradiated with gratification and repose. Again, I have known some people of very modern views driven by their distress to the use of theological terms to which they attached no doctrinal significance, merely because a drawer was jammed tight and they could not pull it out. A friend of mine was particularly afflicted in this way. Every day his drawer was jammed, and every day in consequence it was something else that rhymes to it. But I pointed out to him that this sense of wrong was really subjective and relative; it rested entirely upon the assumption that the drawer could, should, and would come out easily. “But if,” I said, “you picture to yourself that you are pulling against some powerful and oppressive enemy, the struggle will become merely exciting and not exasperating. Imagine that you are tugging up a lifeboat out of the sea. Imagine that you are roping up a fellow-creature out of an Alpine crevass. Imagine even that you are a boy again and engaged in a tug-of-war between French and English.” Shortly after saying this I left him; but I have no doubt at all that my words bore the best possible fruit. I have no doubt that every day of his life he hangs on to the handle of that drawer with a flushed face and eyes bright with battle, uttering encouraging shouts to himself, and seeming to hear all round him the roar of an applauding ring.

So I do not think that it is altogether fanciful or incredible to suppose that even the floods in London may be accepted and enjoyed poetically. Nothing beyond inconvenience seems really to have been caused by them; and inconvenience, as I have said, is only one aspect, and that the most unimaginative and accidental aspect of a really romantic situation. An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered. The water that girdled the houses and shops of London must, if anything, have only increased their previous witchery and wonder. For as the Roman Catholic priest in the story said: “Wine is good with everything except water,” and on a similar principle, water is good with everything except wine.

Or whine.

There are arenas of the fire where discernment is required because hasty application of this principle will sound trite: some have, as I said above, suffered greatly. These are those who have earned their tears, their complaints, their rage.

However, there are other arenas in fire-adjacent places where inconvenience, rightly considered will apply very well — playful stoicism (not internet “stoicism”) or Zen creativity (“beginners mind”) blossom in these merely inconvenienced places. Far beyond those and elsewhere in the country, there are those of us who can creatively, even playfully, say “no” or set a boundary or even argue without fighting, whining, complaining — whose entire demeanor might change if by the light of these flames we reorient our perspective, consider what matters, reapply our gratitude, and rightly consider our daily inconveniences that they might become adventures.

Perhaps even the kinds of adventures where we rush towards the flames to help our neighbors.

For it was our good friends the Lynns whose home burned during Tara’s high school years. And there in the smoldering ashes of their own home, their framed copy of Anne Bradstreet’s poem about Anne Bradstreet’s house lay:

Verses upon the Burning of our House, July 10th, 1666

Here Follows Some Verses Upon the Burning

of Our house, July 10th. 1666. Copied Out of

a Loose Paper.

In silent night when rest I took,

For sorrow near I did not look,

I wakened was with thund’ring noise

And piteous shrieks of dreadful voice.

That fearful sound of “fire” and “fire,”

Let no man know is my Desire.

I, starting up, the light did spy,

And to my God my heart did cry

To straighten me in my Distress

And not to leave me succourless.

Then, coming out, behold a space

The flame consume my dwelling place.

And when I could no longer look,

I blest His name that gave and took,

That laid my goods now in the dust.

Yea, so it was, and so ‘twas just.

It was his own, it was not mine,

Far be it that I should repine;

He might of all justly bereft

But yet sufficient for us left.

When by the ruins oft I past

My sorrowing eyes aside did cast

And here and there the places spy

Where oft I sate and long did lie.

Here stood that trunk, and there that chest,

There lay that store I counted best.

My pleasant things in ashes lie

And them behold no more shall I.

Under thy roof no guest shall sit,

Nor at thy Table eat a bit.

No pleasant talk shall ‘ere be told

Nor things recounted done of old.

No Candle e'er shall shine in Thee,

Nor bridegroom‘s voice e'er heard shall be.

In silence ever shalt thou lie,

Adieu, Adieu, all’s vanity.

Then straight I ‘gin my heart to chide,

And did thy wealth on earth abide?

Didst fix thy hope on mould'ring dust?

The arm of flesh didst make thy trust?

Raise up thy thoughts above the sky

That dunghill mists away may fly.

Thou hast a house on high erect

Frameed by that mighty Architect,

With glory richly furnished,

Stands permanent though this be fled.

It‘s purchased and paid for too

By Him who hath enough to do.

A price so vast as is unknown,

Yet by His gift is made thine own;

There‘s wealth enough, I need no more,

Farewell, my pelf, farewell, my store.

The world no longer let me love,

My hope and treasure lies above.Bradstreet’s poem was one of the only things left after the Lynn’s house fire. They reframed it, singed with soot, in their new house. Though I don’t believe God sends natural disasters — that’s a misunderstanding of the categories — I do think her perspective was rather incredible and, through her, the Lynn’s perspective.

Which, though I didn’t have that in mind with the Chesterton piece originally, for the Lynns and the Bradstreets, this was an absolutely radical application of “an inconvenience, rightly considered.” It would take an incredible amount of courage to apply that vision.

So it was precisely the poem I read to the stone sculptor Abraham Mohler when standing in the ashes of the church — part of the Lucas Schoolhouse — that had been his studio:2

Bradstreet’s poem served Abe well as did some other classic texts like that of the three men in the fire who miraculously became four; your mileage may vary.

But Chesterton’s — and therefore Bradstreet’s — pieces are not the only eels churning in my eel barrel of emotions whenever a new disaster throws a new one into its dark slimy waters.

I think of everyone from firefighters to photo journalists to the mildly inconvenienced who will have this unique opportunity to love their neighbors who are, invariably, devastated by this fire. Particularly if — as is almost certainly the case — some insurance companies do nothing.

At least one major company will almost always do nothing in these situations. That’s what happens in a society whose only value is the proximate good of wealth as opposed to the ultimate goods of beauty, truth, goodness, and the unity of identity.

I think of how opportunistic cynicism which preys upon the denial stage of grief (Alcoholics Anonymous would call this Step One: admitting there’s a problem) makes every single one of these disasters worse.

On the opportunism side, I think of how none other than this town’s own Los Angeles Times reported how Exxon Mobil for years publicly denied global warming, but quietly predicted it and planned on it for the projections, which required Arctic ice to melt so that they could drill even more starting in 1977; of their hiring the exact same lobbyists the tobacco industry hired when the tobacco industry wanted to convince the American public that tobacco doesn’t cause lung cancer; of disaster scammers; of politicians exploiting disasters for political points; of “thoughts and prayers” contradicting those very thoughts and prayers with opposite action like selfish water use or willful and habitual inaction (for this reason, the ancient confession begins “I confess to Almighty God that I have greatly sinned in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have left undone and in what I have done”); of activism refusing to appeal to the highest consciousness — Reason per se — with the very holy thinking and praying that predicates all great collaborative activism, especially with praying folk who need good teachers with experience in activism (“…in my thoughts”).

On the denial side, I think of a handful of my good friends who remain climate change skeptics yet refuse to personally evaluate their own current stage of denial in the teeth of mountainous proof; of my good friends who are climate scientists who have all but given up on changing the minds of those with an equal and opposite direction of the denial stage of grief; of the folks who ignored the meteorological warnings prior to the Joplin tornado; of my father who — thanks to the politicians whose hands remain stained with dad’s blood — ignored medical advice and didn’t get a vaccine for COVID, which killed him the same way it killed my New York neighbors here and neighbors elsewhere. We had the exact same refrigerator trucks — "temporary morgues” — by every funeral home here in Brooklyn that we had in Joplin after the tornado.

Yes, cynicism and opportunism worsens disaster by preying on the denial stage of grief. Admitting there’s a problem and reforming our own hearts is the first stage of helping.

And so my inner eel barrel churns: I think locally too of the looters in Joplin and Katrina and Galveston as well as the spray painted signs of “You Loot, We Shoot.” I think of out-of-towners who preyed with and upon similar behavior when Tara’s hometown Ferguson protested after an assassination (those who looted from in town, those who came from out of town to loot, those who reported only on that and not on the long history).

Another eel slops into my feelings barrel: I think of friends who lost everything and then got it all back quickly in the Joplin tornado and other friends who only lost some of everything and received nothing back, only to relocate to Alaska and get hit by their first blizzard. And then of similar things that happened to my new Alaskan friends (from the documentary work) during the Anchorage earthquake. I feel so, so strongly. I remember too working with fifteen other guys in the sludge following Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans to move an entire wall of a house out of a clearing where the surge had swelled. Probably the heaviest thing I’ve ever lifted in a group. There’s an old picture of me in Galveston perched on a pier pole that I cannot find, but that kind of ennervating physical service stands out stark in my mind.

In this, the current of my inner eel bucket forms a kind of pattern. So my mind shifts towards hope.

An odd kind of hope. It isn’t optimism.

Did you know that the Joplin Tornado was — at least at the time — the fastest recovery on FEMA’s record? I’ve seldom written about this, though I talk about it in person often. One of my friends works at NASA — he jokes about owning 1/100th of an Oscar because he was on the visual team for Interstellar. He does similar work for NASA. He came to town with his husband and while here, we met some of their colleagues at the Neil DeGrasse Tyson planetarium. Some of the scientists there had a speciality.

The Joplin tornado.

They were studying it from space, you see, the weather patterns:

Mainly because it was the only tornado to pull up grass. That wasn’t a thing. They almost upgraded the scale from EF5 to EF6 because it was an EF5 with two EF2s churning inside of it like a blender — sort of a tornado three body problem. How do you visualize this for folks? There were places afterwards where the grass blades stuck out clean from concrete, you could run your hand down them like vertical astroturf. Some 2x4s were sticking clean out of curbs, no cracks. St. John’s — the massive hospital tower — rotated a quarter turn.

The tornado’s trajectory was the length of Manhattan and half the width. Conceivably here in NYC, a similar situation could have killed a couple million:

So when those specialists said they wanted to talk to me, they’d never encountered someone who had lived through the tornado. Personally.

They had the passionate curiosity that only specialist scientists can have and only after asking a million curious questions of me did they check to see if it was insensitive. It was kind of hilarious, to be honest, but I happily answered their questions about the destruction, the rescues, everything I could remember.

But there was one question they didn’t know to ask.

So I gathered their attention and asked, “Do you know why it was the fastest recovery on FEMA’s record?”

They didn’t know. They did lean in.

Let me tell you this story. A story that starts many, many years prior to the Joplin tornado. Do you have your coffee or tea nearby?

Hwæt. Sit back and listen:

In the decade prior to 2011, streets in Joplin were crumbling. Windows were falling into disrepair. Folk owned homes in desperate need of roof work. Weeds broke up concrete. Some lawns grew into tall grass prairie (which is good for climatological and biodiversity reasons, but this was more the unmanaged sort of tall grass prairie, if you get my drift). Chainlink rusted. Downtown crumbled. We had no coffeeshops. We had no Chipotle. We literally in 2005 had to lobby through a massive petition to get a Starbucks and a Chipotle. I remember the petition. I remember signing it, having grown up without internet until 2005 not unlike my grandpa growing up with an outhouse through the 70’s. In retrospect, there were probably better ways to spend our activism than lobbying what would become one of the largest fast food franchises in history.

Something productive like beard growing competitions named Whiskerino run by friends in Nashville that turned into a national fad.

I’m joking, of course, at least a little, but that does paint a picture of the times. The economy was recovering pretty radically from the Bush-era housing crash, an economy that would continue through the beginning of 2020, when the market would promptly crash again as it’s preparing to once more next year. Things were weird in college towns like Joplin.

In any case, we started a few things that helped.

One of them was a visual art collective planted by the Limner’s society from NYC — this long tail connection would land me in NYC through other means. That group dwindled down to just me and Mark Neuenschwander before, through steady monthly faithfulness, it blossomed into probably 150 artists on the fringe, long term. These are the folks that banded together to form the first Third Thursday art walk, who started all of those early coffeeshops and roasters, who painted murals, who hosted photo booths, etc. I’ve started a similar group of artists here in Brooklyn. We’re already up to almost 200 writers, dozens of filmmakers, musicians, etc. It’s a model that Tara and I might write about in depth if time and opportunity present themselves.

Another thing that helped was the Great Day of Service.

The Great Day of Service started with a partnership through the ministerial alliance and eventually grew to where every church I knew about in the area as well as the Synagogue and the Mosque would shut down one weekend in October. Rather than having services, everyone would don shirts and take on quadrants and neighborhoods of the city. Sometimes your team would mow neglected lawns. Sometimes your team would pull weeds on neglected streets. Often your “team” was your small group or 12-step recovery group. If someone struggling with hoarding needed help, you’d fill a 40’ dumpster. Bricklayers laid bricks. Contractors did free labor for those who couldn’t help it. Folks with ATVs hauled downed trees.

I roofed houses with folks, painted, swept, mopped. I think at one point I saw some rather big backhoes get involved. What’s the noun of assemblage for chainsaws?

A steeplechase of chainsaws?

I daren’t use Ai even to illustrate a steeplechase of chainsaws — I would wield this power from a desire to do good, but through me it would wield a power too great and terrible to imagine. But it’s tempting. It’s tempting…

Sure, a steeplechase of chainsaws.

The city looked orders of magnitude better after a single day spent with every religious institution in Jasper county collaborating on high-ethical service, special beneficence and general beneficence united. There was follow-up, of course. But The Great Day of Service really knocked out gobs and gobs of surface issues so that deeper issues could be dealt with throughout the year. That experience translated into more and more of Joplin’s white vans showing up in disaster zones in other cities throughout the rest of the calendar year. Folks knew Joplin citizens as those who showed up when their down was hurt.

So by the time the tornado hit, we had years of experience collaborating as neighbors, churches, friends, foes, and everything in between. We had years of experience taking care of issues that arose, cosmetic or otherwise. We had years of collaborative partnerships with all sorts of other towns like when we went to New Orleans to serve after Katrina, Galveston after Ike, not to mention the large body of international nonprofits serving all over the world on issues ranging from sex trafficking of little boys to water rights to farming to media.

The EF5 tornado hit Joplin on graduation Sunday. Again, it’s a college town. It hit between the graduation ceremonies and the dinner celebrations, so loads of folks were out of the main zone. The disaster warning got off barely with 30 minutes to spare and folks ended up under the awning of houses — as I said in the song The Wreaker, which I’ve only ever performed live (it’s a weird song), “all our homes: so many triangles cut out of squares.”

Here’s the only existing live version from Rockwood Music Hall:

That saved lives, that 30-minute warning to “take shelter in the center room of the house” warning. So, frankly, did prayer — like as a data set. We have so, so many documented stories of folks literally in midair being rescued by beings of light. Of children yanked from cars and their mother’s grasp only set down by such creatures in a cow pasture somewhere. Of “fourth man in the fire”3 moments in those ramshackle homes.

Wasn’t enough, of course. Assuming the veracity of those accounts from the “thoughts and prayers only” crowd, it seems there were only so many angels on loan in Joplin that day, however prayerful.

And so.

When you kick a downed beehive, bees escape and attack the source of the destruction.

A decade of art walks and Great Days of Service were unleashed upon the worst tornado in history. I remember how many times we would go back to the map at College Heights and see precisely where the national guard had, more or less, formed a blockade like a shield wall while all of the volunteers were using CB radios to get around them and pull still more people out of the rubble. It was collaborative, but as The Independent Review said, eventually dialing back the regulations on volunteers helped.4

Tara and I were babysitting for a hospital administrator was called back for triage, and that field hospital was something else.

Those same ATVs showed up, those same backhoes, that same steeplechase of chainsaws. Folks were used to pulling branches out of yards, what were a few more? Folks were used to putting out fires and mopping, what was a little more water and fire? The Whole Community response became a model for FEMA.5

Joe Klein of TIME Magazine came through only a few months later for the annual Great Day of Service:

His pulpit, which he sat upon, was a blue recycling tub filled with household supplies. He didn’t give much of a sermon, just instructions for the work that was about to take place–thousands of people had come to Joplin from all over the country for the church’s eighth annual Great Day of Service.

…The message was simple, powerful….but not nearly as powerful as the sight of people of all ages, wearing white t-shirts, gathering up into work teams and spreading out around town to help people who were still suffering from the ravages of the tornado and others who were just suffering because they were poor or infirm or elderly. “We will not make this about doing a job,” St. Clair went on, “Lord, save us from ourselves. We will make this about the people whom we are about to serve.”

Later, St. Clair–a kindly man with pale blue eyes, whose righteousness seemed entirely free of self-righteousness–explained to me that years ago the church had made a mission of serving outside its walls. And after the tornado, the church — which was not damaged — moved more deeply into the community. “Now our church is no longer defined by walls. It exists outside the walls. Our church is the service that we do.”

…When the Kendalls had been reunited, St. Clair went out to help with the cleanup at a nearby senior citizens center. “The thing I really remember was how quiet it was,” he said. “There was no panic. People just went right to work. The silence was the common grace of God falling over the community.”

Afterwards, Katy Steinmetz and I went off with one of the work groups. They came from a Baptist church in Morgantown, West Virginia, and set up shop at the corner of 19th street and Murphy Ave. with rakes, brooms, lawn mowers and trimmers. This was an area of modest homes near the path of the tornado (and, I must say, the tornado path still looks something like Hiroshima). There wasn’t much damage but the West Virginians went door to door asking people if there was anything they could do for them. Soon mowers were growling and leaves were being raked. I stood there watching these people, feeling uncomfortable, unfulfilled. I picked up a broom and started working on the sidewalk, with a fellow named Todd who told me that he and family go on service missions regularly. Last summer, they went to Nicaragua. Todd was a terrific guy. We worked together well. It was good work.

It ended up setting records and the town is a thriving area now with a vibrant arts scene, a vibrant culture. Not that it didn’t have one before, but the ownership of place ended up defining them.

That in mind, I could move on from Joplin to point to the folks we know from Tara’s hometown in Ferguson. How the community came together. Antigone in Ferguson played here in NYC, a version of Antigone starring people from all walks of life in Ferguson — cops, students, parents of victims.

Of the folks that finally realized there was a problem. For every Pruitt-Igoe building and instance of redlining, there have always been visionary community builders in St. Louis like Love the Lou that operates similarly to Bobby Constantino’s work in Dorchester and Archbishop Joseph E. Ritter who seven years before Brown V. Board of Education “publicly said he would excommunicate any St. Louis Catholic who continued to protest the integration of parochial schools.”6

And it’s not merely there either. How many old-school New Yorkers have we met who said the moment people took ownership of the place, those courageous people defined that moment. The 9/11 survivors I know here say the exact same thing as, more or less, did colleague Todd Komarnicki, who wrote the script for Sully about the miracle on the Hudson. Of the way the long obedience in the same direction — locals serving the community came together to rescue. That played out the exact same way during Hurricane Sandy the year before we moved here. And it even played out in how Fred Danback saved 12,000 lives on September 11th, according to Makoto Fujimura in Culture Care:

IN THE EARLY 1960S, FRED DANBACK CAME HOME FROM THE KOREAN WAR TO WORK AT ANACONDA WIRE AND CABLE, A COPPER WIRE FACTORY IN HASTINGS-ON-HUDSON, NEW YORK, THIRTY MILES NORTH OF MANHATTAN.

It was a booming enterprise. But he soon became troubled by what he saw at the factory. To restore beauty to the river he had grown up with, Danback became a whistleblower against his own company.

In a PBS interview with Bill Moyers, Danback said, “I seen all kinds of oil and sulfuric acid, copper filings; my gosh, they were coming out of that company like it was going out of style…” He said that shad fisherman started to lose “their business because there was oil in the water that would cause the fish to be contaminated with it and the Fulton Market refused to take their weekly catch… [Anaconda] and other businesses were polluting a river and hurting a second business, the shad fishermen. I didn’t think they had the right to do that. It used to really infuriate me. I became obsessed with fighting pollution…”

Fred complained to the managers about his fisherman friends’ plight. Each time he did, it seemed, he got demoted. He ended up as a custodian. But Fred never gave up. He worked in that custodian role, literally pushing his broom into every room of the company. He also took copious notes and made maps of the company. What was intended to be a punishment ended up as the best possible opportunity to spy on the company. He had all the keys!

There were few pollution laws at the time.

Fred and a few other pioneers of the environmental movement decided to sue Anaconda under an archaic law called the Refuse Act of 1899, which Fred found while cleaning the local library. In 1972, when the U.S. Attorney’s Office found a way to prosecute Anaconda, they used Fred’s maps and notes as evidence.

“The company was fined $200,000 under the Refuse Act of 1899, you know… even today for a polluter to be fined $200,000 is a big event. Back in the early 1970’s, it was a huge event. It was like a thunderclap,” said Fred later.

Today, three million striped bass go up and down the Hudson because Fred’s efforts led to changes in the laws of the land.

There’s not a day I do not think of Fred Danback. As I used to jog on the promenade of the river, I thanked God for Fred’s sowing the initial seeds of sacrifice. As I follow the bluebirds’ nesting behavior at my farmland now, I think of his work to create cleaner rivers and air. But there’s more to the story.

As the horrific news began to come out on the airline attacks of September 11, 2001, the initial estimate of those who perished was twelve to fifteen thousand. In the next few days, however, the numbers kept decreasing, eventually to 2,977—still unbearable, surely. I have a theory about why the initial estimate turned out to be so wrong.

September 11 was the first day of school. There were eight thousand students around the World Trade Center towers. Parents had just dropped off their children—as did my wife with our three—when the sinister shadow of the first plane passed over them in the schoolyard. Few of these parents made it to work. Those who did came back down the step right away, like many of our friends, ignoring the fatal direction to “stay where you are.”

You may not see the connection yet with Fred Danback, but there is a direct link in my mind. Here it is: All of the schools around the towers were built since the late 1970s. Because Danback was willing to be demoted, the river became cleaner. Because the river became cleaner, the parks around the river became attractive. Because the parks were good, young couples becoming parents decided to stay in their small Battery Park apartments instead of escaping to suburbia. Because of the resulting tremendous increase in the student population starting int he late seventies, the city built all those schools.

I am convinced Fred Danback made a difference made a difference on 9/11. One person with the courage to be demoted, one person willing to sacrifice for the restoration of beauty, created a ripple effect in culture with immeasurable generative influence. The effects of his action cannot be measured but can only be told in how we live our lives—and so it is worth noting that the children of 9/11, including our three, grew up to be enormously resilient, creative, and community-minded.

Culture Care actions, similarly, cannot be measured by typical metrics of effectiveness and efficiency. The measure of success must be in how our sacrifices to make Culture Care possible manifests itself in the lives of our children.7

Or consider Tunisia, where Tara and I spent our honeymoon teaching a summer camp to the children of a nonprofit so that they could find respite and recovery — both therapy and spiritual direction — the summer before the Arab spring when all of their work humanizing and educating their neighbors in the teeth of the security state would bear much fruit.

Do I have time to tell you about the work I witnessed in Galveston after Hurricane Ike? Or of the way my late father would chase disasters around the country, looking for a local carpenter’s union who needed help? Who went into debt helping those in recovery?

This story gets repeated over and over again: culture is what we make, from where we are, in order to build community. And neighbor love — especially the stranger, especially the foreigner, especially when we turn our xenophobia into philaxenon — can make or break a disaster.

Moving from Joplin and NYC and the rest, I could point to the best parts of the recovery of Katrina.

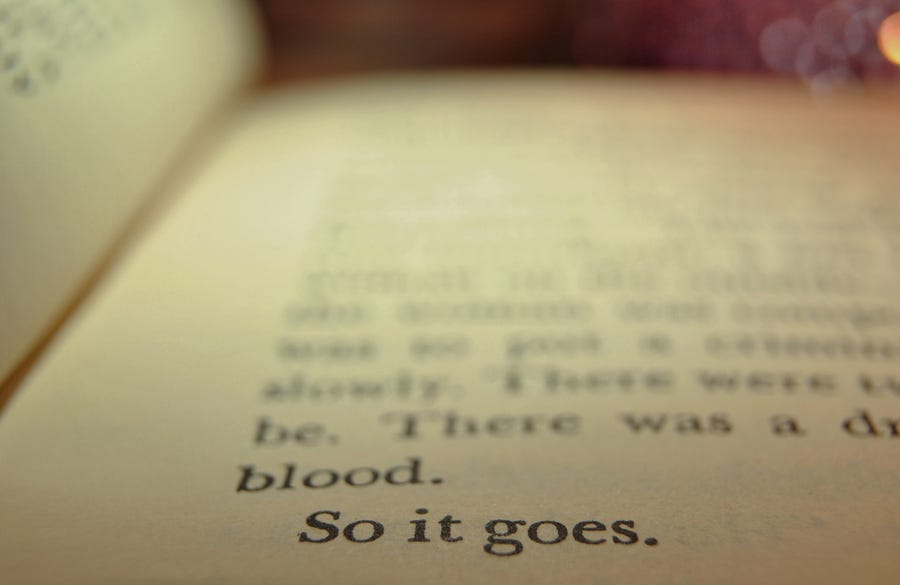

There’s a book on my shelf entitled Paradise Built in Hell by

(assuming that’s the same person on Substack). Rebecca writes of multiple historical instances where, as the subtitle of her book says, “extraordinary communities arise in disaster.” She focuses on the San Francisco earthquake, the Halifax explosion, Mexico City’s earthquake, New York in grief and glory, and New Orleans.What difference does it make, according to Rebecca?

Thousands of people survived Hurricane Katrina because grandsons or aunts or neighbors or complete strangers reached out to those in need all through the Gulf Coast and because an armada of boat owners from the surrounding communities and as far away as Texas went into New Orleans to pull stranded people to safety. Hundreds of people died in the aftermath of Katrina because others, including police, vigilantes, high government officials, and the media, decided that the people of New Orleans were too dangerous to allow them to evacuate the septic, drowned city or to rescue them, even from hospitals. Some who attempted to flee were turned back at gunpoint or shot down. Rumors proliferated about mass rapes, mass murders, and mayhem that turned out late to be untrue, though the national media and New Orleans’s police chief beleived and perpetuated those rumors during the crucial days when people were dying on rooftops and elevated highways and in crowded shelters and hospitals in the unbearable heat, without adequate water, without food, without medicine, and medical attention. Those roomers led soldiers and others dispatched as rescuers to regard victims as enemies. Beliefs matter — though as many people act generously despite their beliefs as the reverse.

Katrina was an extreme version of what goes on in many disasters, wherein how you behave depends on whether you think your neighbors or fellow citizens are a greater threat than the havoc wrought by a disaster or a greater good than the property in houses and stores around you.

— Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit, p1

She goes on to point to how often the altruism of…

…young men who took it upon themselves to supply water, food, diapers, and protection to strangers stranded with them; of people who rescued or sheltered neighbors; of the uncounted hundreds or thousands who set out in boats to find those who were stranded in the stagnant waters and bring them to safety; of the two hundred thousand or more who (via the Internet site HurricaneHousing.org int he weeks after) volunteered to house complete strangers, mostly in their own homes, persuaded more by the pictures of suffering than the rumors of monstrosity; of the uncounted tens of thousands of volunteers who came to the Gulf Coast to rebuild and restore.8

She offers us that choice. The choice between Cain, who killed his brother, and those who keep the chaos at bay. Of those neighbors who didn’t know one another during the hurricane in Halifax, Nova Scotia who woke up the next morning to talk and aid and cook and check in on elders. Or of a friend who slept upright in a small diner with strangers during the dense fog in California. Or how in the wake of the Loma Prieta earthquake, so many had cooked through their thawing frozen food to host barbecues in the street.9

On [Amelia Holshouster’s] third day in the park [after the San Franciso earthquake], she stitched together blankets, carpets, and sheets to make a tent that sheltered twenty-two people, including thirteen children. And Holshouser started a tiny soup kitchen with one tin can to drink from and one pie plate to eat from. All over the city stoves were hauled out of damaged buildings — fire was forbidden indoors, since many standing homes had gas leaks or damaged flues or chimneys — or primitive stoves were built out of rubble, and need. Her generosity was typical, even if her initiative was exceptional.

Holshouser got funds to buy eating utensils across the bay in Oakland. The kitchen began to grow, and she was soon feeding two or three hundred people a day, not a victim of the disaster but a victor over it and the visitors from Oakland liked her makeshift dining camp so well they put up a sign — “Palace Hotel” — naming it after the burned-out downtown world. Humorous signs were common around the camps and street-side shelters. Nearby on Oak Street a few women ran “The Oyster Loaf” and “Chat Noir” — two little shacks with their names in fancy cursive. 10

Solnit shows over and over how this develops into little utopias. Of mutual aid marketplaces, lifeboats, chainsaws coming to the rescue from those who truly love their neighbors.

It is by its very nature unsustainable and evanescent, but like a lightning flash it illuminates ordinary life, and like lightning it sometimes shatters the old forms. It is utopia itself for many people, thought it is only a brief moment during terrible times. And at the time they manage to hold both irreconcilable experiences, the joy and the grief. This utopia matters, because almost everyone has experienced some version of it and because it is not the result of a partisan agenda but rather a broad, unplanned effort to salvage society and take care of the neighbors amid the wreckage.11

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always heading.

— Oscar Wilde

I disagree with Wilde’s assumption that Utopia will somehow be perfectly engineered in a universe of entropy, but I have some other hopes about that good country to which we are all headed. We’ll get to that in a moment.

But it takes courage to face the danger for our neighbors.

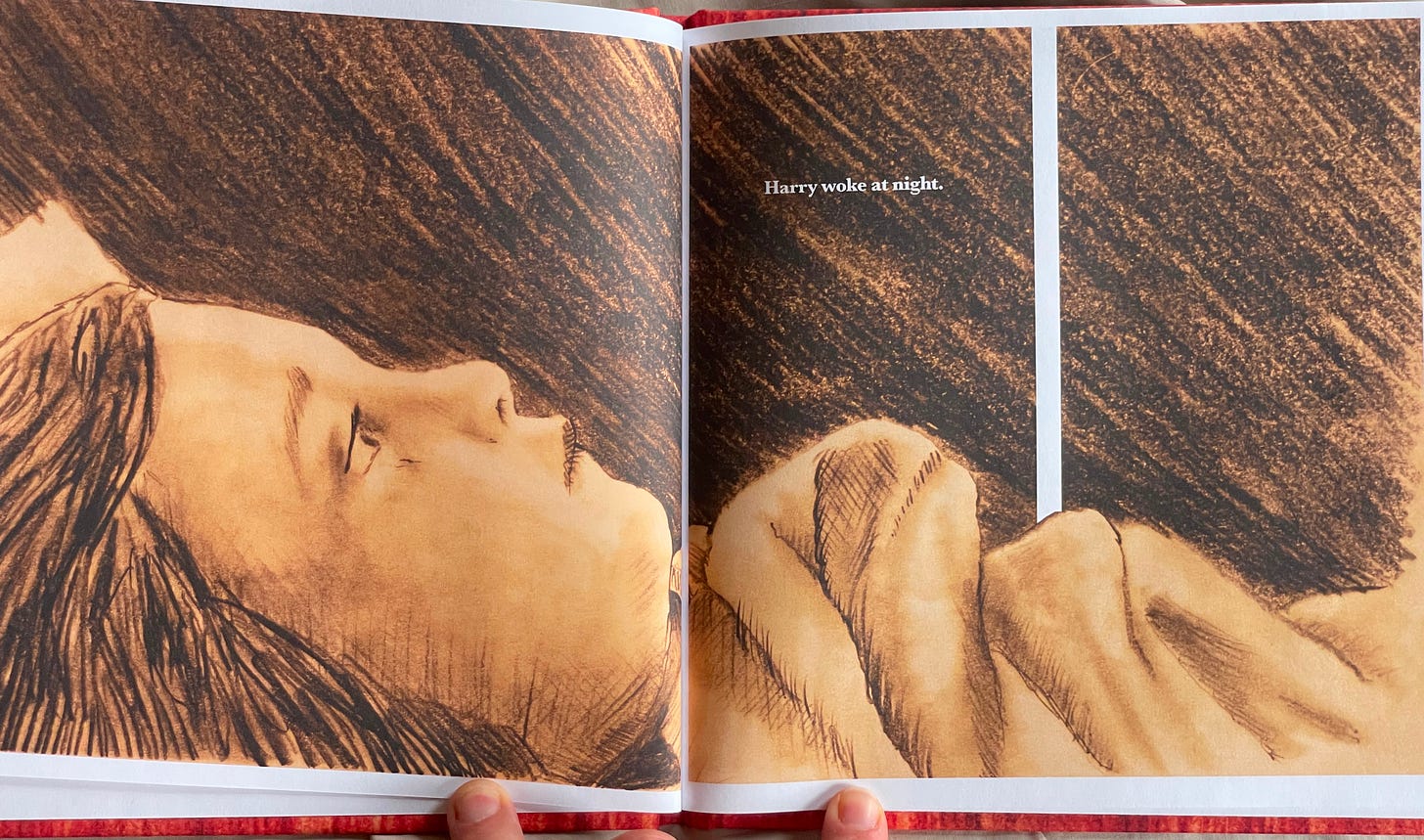

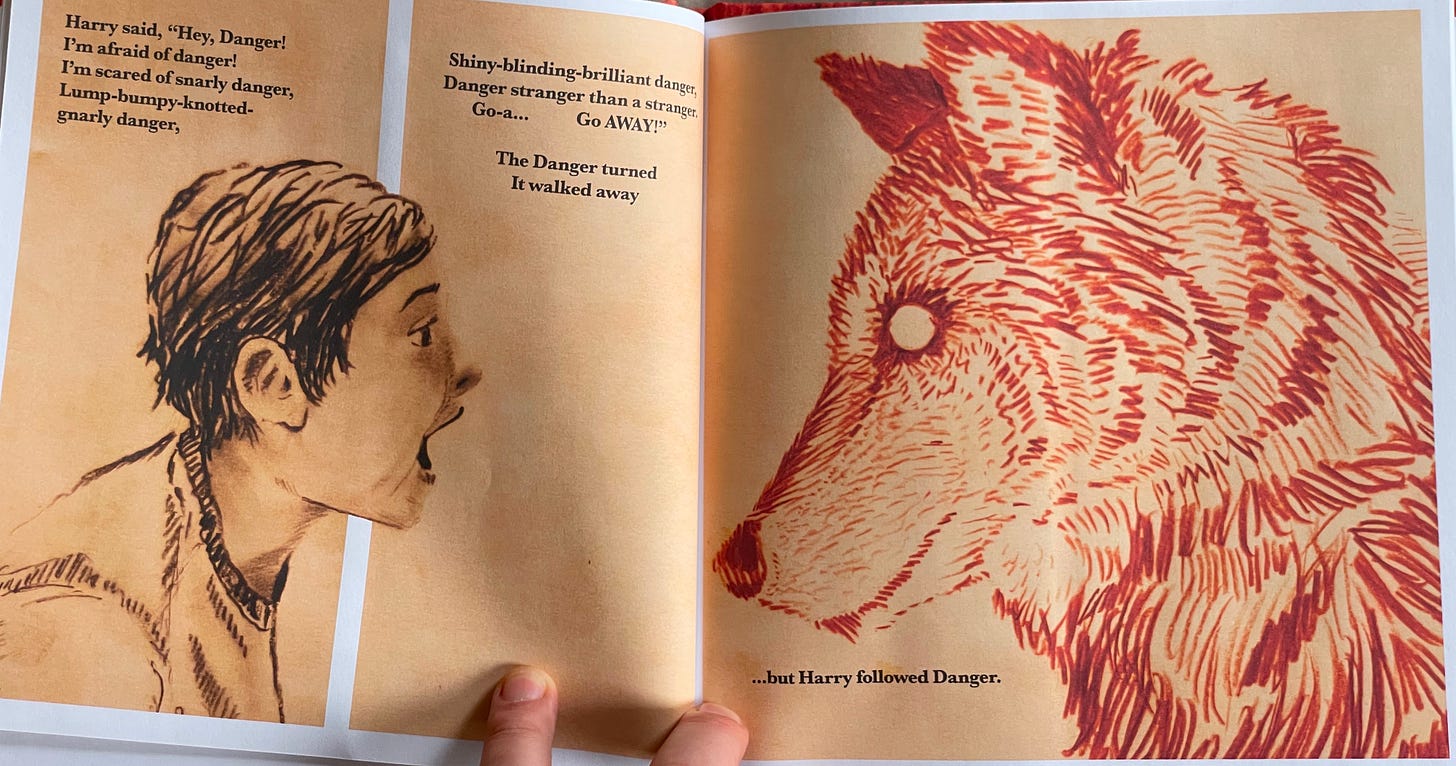

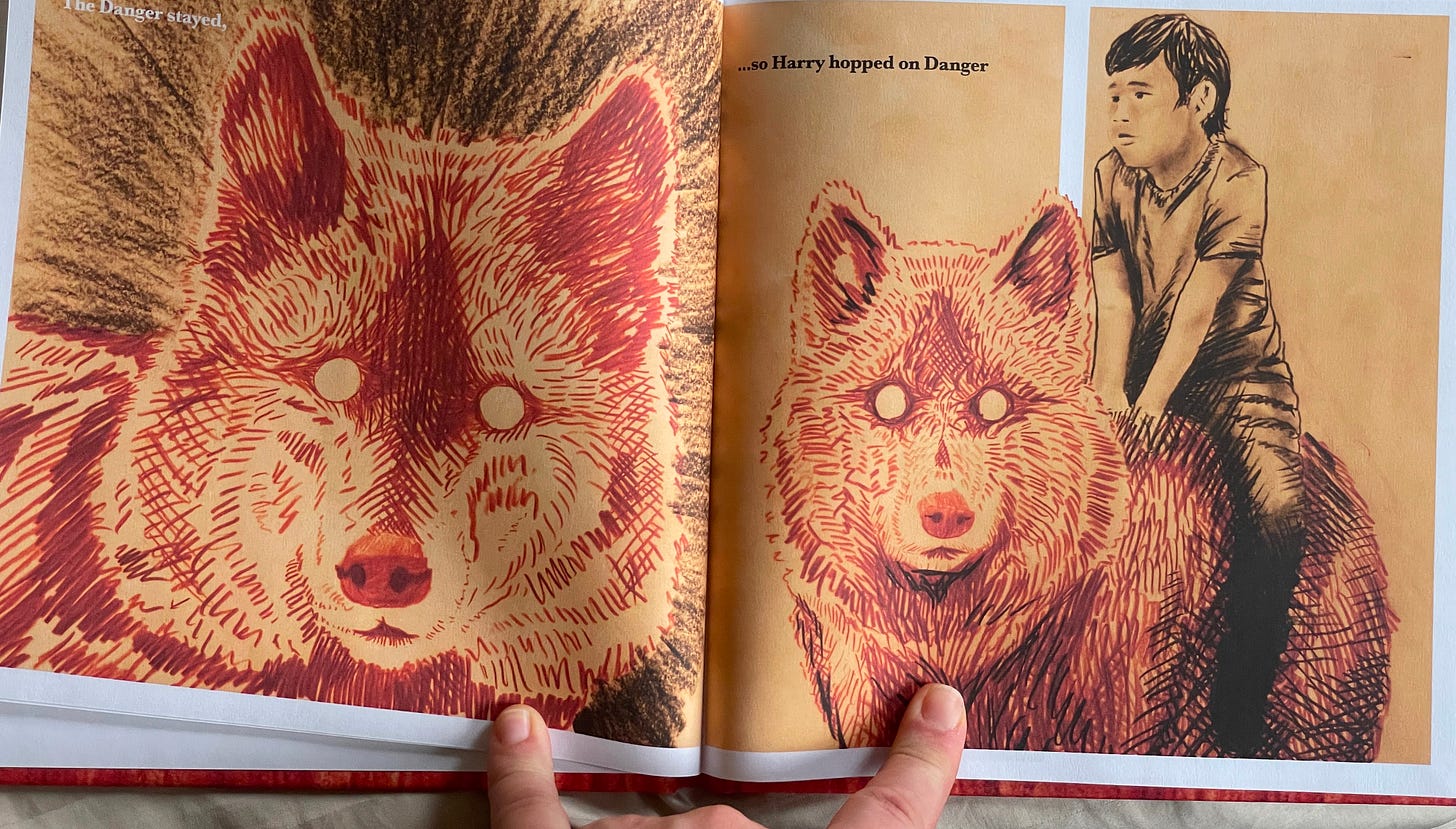

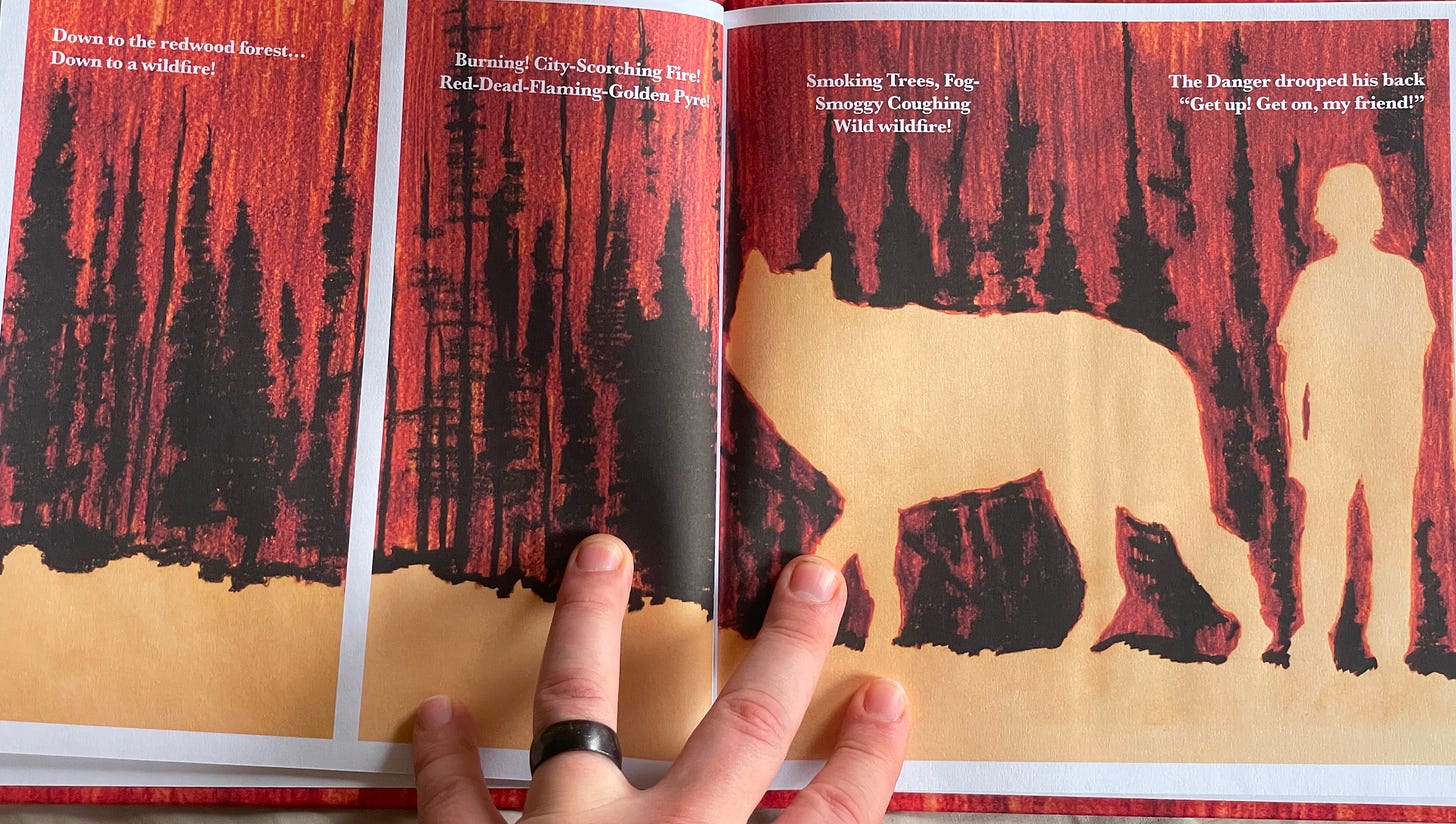

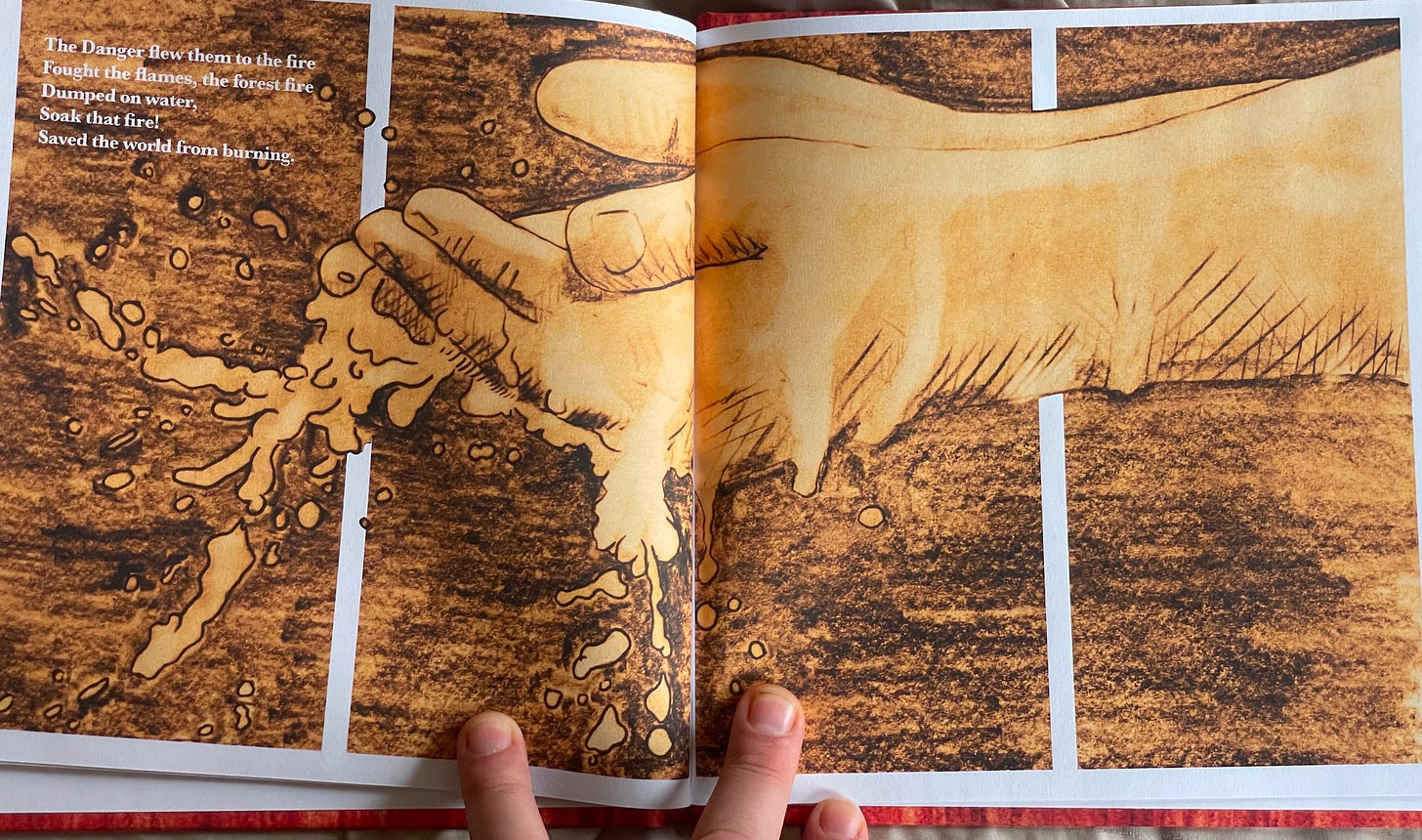

For this very reason growing out of my experience with the Joplin tornado, I wrote Harry Rides the Danger. Granted, the metaphor was fire. My buddy Mark 9, the commercial photographer your company or nonprofit should hire before any other, had a son named Harry. They lost their entire home in the tornado and, as a result, all of his cameras and lenses.

Shortly after the Joplin tornado, very young children at College Heights started playing on the playground spinning around and saying, “The tornado got me! I’m DEAD!”

Parents being parents — the same creatures who fear memento mori and therefore often disallow obviously beneficial play acting like that found around Dia De Muertos — immediately told the children to stop. The children playing pretend mass death had triggered the adults.

Luckily, emergency trauma therapists were on site saying, “No, let them play. Play and pretend is how they process trauma: they’re debriefing. This is therapy for them.”

And so the kids continued to play dead. Ring around the rosie…

A few months later, we had a summer festival for College Heights at Carousel Park. (Or as one curmudgeonly bearded friend who also did Whiskerino called it, “Tetanus Park”). There we rallied to celebrate for the first time in a great while.

I arrived early with Tara and Mark’s son Harry showed up asking Uncle Lance if he could ride the rides with him. We chose a kiddie coaster and Harry got off super excited. He had this nervous tick that would take over him whenever he was excited: he’d clench both fists and wring them before his grin. He did that then, post kiddie coaster, as he approached his dad.

“Dad?”

“Yeah buddy?” Mark asked.

“I… I ride… I RIDE THE DANGER.”

And it clicked. I wrote this children’s book about facing the danger the way the Joplin community responded and another tornado survivor, Tony Otero, illustrated it.

See we’re all scared sometimes of abstract unknowns. Of the fear of fear. Of the abyss. The unseen horrors that can take us — be they fire, flood, storm, or worse.

These fears manifest as the worst bits, almost disconnected from all of the rest of our lives.

And even sometimes at our best when we admit our fears, we still deny it. We hide. We want to flee them or smash them or freeze.

But our best, highest self doesn’t want to run or hide or fight. Our best, highest self doesn’t want to give in or become authoritarian. Our best highest self wants to take a calm authoritative assertive response and interact in peacemaking love and dialog. Assertive peacemaking.

If we do that, we can find ourselves in extraordinary situations. Moments when disaster strikes.

In those moments, if we face danger for the sake of our neighbors.

We can become something truly incredible. Wise beyond our years and able to assert ourselves over disaster for the sake of all of the humans we touch, both those we like and those we don’t. The alchemists and Arthurian romances had a phrase: in sterquiliniis invenitur. In filth it will be found. The knights of the round table had to enter the deep, dark scary woods of the fae in search of the holy grail through the part of the forest that appeared worst to them. If they struggled with lust, they had to enter through a brother. Greed? A dragon’s hoard.

And only by throwing off the old self in the house of filth could they find the thing they truly wanted. The thing they most wanted to find would be found in the place they least wanted to look.

Are you afraid of your neighbors? Your interstate or international neighbors? The person on the other side of the road or street or county or country or social media flame war or ballot box?

That filth — that fear — is trying to tell you something. In sterquiliniis invenitur.

In case we have any kiddos or folks in California processing the fire, I recorded this for free. Originally wrote it to help kids process the Joplin tornado, but as fire is the element in it, it might help explain bravery, firefighting, etc:

Were all of the above not the case, I still keep an eye on CalFire. Fire burns in my memory not light, but Promethian shadow, seared there first in my childhood through my random perusal of what few books I could find in Southern Illinois in my childhood, then through my DO 525 mythology class I custom made for myself to study one-on-one with the academic dean of my alma mater. I’ve consumed as much of our collective mythologies from that moment onwards, often seeing where they dovetailed in history. It’s why I enjoying Patrick Rothfuss’s Name of the Wind and Brandon Sanderson’s Starlight Archive more than most (though I tend to agree more with Sanderson and less with Rothfuss about the implications of μῦθος in the mouth of a ἵστωρ).

κατάβασις is the word we’re looking for — the part of the old creed that reads “he descended into Hell,” but applies to many, many myths.

Enkidu, whom I cited in the piece on Neil Gaiman’s Prostitutes, offers to recover the drum and drumsticks of Inanna and Gilgamesh which fell into the Netherworld and finds himself held forever. Sometimes these myths end up like that — a heroic rescue ends up tragic. Or you have Ishtar attempting to overthrow her sister, queen of the underworld.

The Tale of Setne Khamwas and Si-Osire comes to mind. Setne and Si-Osire watch a couple of funeral processions. The first features a rich man well-attended, vibrant funeral. The second features a poor man hauled off alone to the crypt.

Setne says the rich guy probably would have been quite joyful, having so much crying and hollering over him. But his son Si-Osire disagrees. He says he’ll reveal the fates of both: the unmourned poor, the mourned rich.

So they go to Duat, land of the dead.

There in the seventh hall of the land of the dead, they witness the court of Osiris, Anubis, and Thoth. One extremely lauded and well-dressed servant attends Osiris. Setne says this one must hold the highest rank. But goodness and evil done in life are adjudicated on scales by the three gods: the well-heeled man was the unmourned poor because the wealthy dead man’s "burial equipment" had been stripped off and offered up to the poor man, whose goodness was found substantial. Si-Osire concludes "He who is beneficent on earth, to him one is beneficent in the netherworld. And he who is evil, to him one is evil. It is so decreed forever.”

So is this repeated all over the place.

And you end up with rescue in instances like Adonis rescued by Aphrodite, Theseus and Alcestis rescued by Heracles, and Orpheus’s famous attempt to rescue Eurydice, which was turned into What Dreams May Come and Hadestown. For Orpheus, his angel already lived in hell and so his paradise was already there, waiting to be returned.

In the Vedic religion, the Panis stole cattle and hid them in the Vala cave. Indra uses his song chants to heave the cave in two, releasing both cattle and the dawn — winning light for all mankind.

Similarly in Buddhism, you have Monginlin also known as Mulian or Radish. Prior to becoming a Buddhist, Radish goes on a journey — really a business trip. Are Buddhists even allowed to mark “pleasure” at customs?

He gives his mom some cash to feed monks and beggars. But mom hoards it. Radish returns, she dies, and so the Jade Emperor turns her over to Yama, ruler of the netherworld. Yama sends mom to the deepest level of hell for this.

So what’s Radish do? Become a Buddhist and wield his newfound power to go to heaven. His dad said, “Hey, did you know your mom’s suffering extremely in Avīnci Hell?” It’s the worst of the purgation.

So Radish descends encountering these charming, lovely ox-headed devils that goad sinners across the river kind of like the Styx into hell. There they have to hug giant burning copper pillars that burn away their chest bones. Cheery. When Radish finally finds mom, she’s nailed down with forty-nine iron spikes. So Radish hunts down Buddha for ait. Buddha gives him a rod to smash prison walls and release the prisoners of hell to a higher reincarnation. Nice.

But mom’s still stuck.

She’s reborn instead as a hungry ghost never to be satiated due to a tiny neck. Radish attempts offering food on the ancestral altar, but that just explodes the second it touches her mouth.

Buddha said, “Radish: you and the sons give a feast in these yülan bowls” and sets up this formal feast day. So mom comes back something like the grim — the black dog. Seven days and nights he receipts sutras and his mother returns as a human, then ascends into heaven.

There are others, of course. In the original Hell — the Norse one, not the Sheol / Hades / Vale of Hinnom of the Bible translated as “hell” — it seems like every single god of their pantheon is chomping at the bit just to spend some time in the flames. Part of me wonders if that’s because the Nordic states are so cold, though in Dante’s version the lowest level features Satan encased in ice.

But you’ll remember in Dante’s version we have what C.S. Lewis calls one of the earliest science fiction effects: Dante, the protagonist of Dante’s self-insert Virgil fanfic, hits Satan’s frozen belly button and starts climbing up.

Why?

Because he’s reached the center of gravity and purgatory (1 Cor. 3:12-13) begins there. This is exactly what C.S. Lewis says in The Great Divorce and what George McDonald says in Lilith:

That paradise begins in Hell because Being, fundamentally, is good.

And so one of the most striking images of paradise built in Hell and of angels braving flames to rescue us, of course, comes from certain conceptions of atonement and not necessarily from others. Granted, there are the sadomasochists in atonement theory, those who seem to think that Jesus died for an infinitely powerful demon worse than Satan requiring a retributive death penalty for that time you stole a snickers. These are the kind of folks who believe that God himself sends natural disasters, the kinds of folks for whom the best part of this twisted version of the Christian story is the gated community. Is it ironic or coincidental that much of the actual BDSM community often finds this vision so appalling? Could a wiser soul could learn something about both communities through that visceral contrast?

In any case, the striking image I’m referring to, rather, comes from Christus Victor types who follow the fathers, particularly in the Eastern Orthodox community, translate the word as “manumission fee,” the word meant for the price paid to liberate slaves. Generally, the fathers simply said this is the price — it’s the cost of things. It costs resurrection to defeat death, which by implication means that the risen one must first die. Death is entangled in the very definition of the phrase “resurrected from the dead bodies, firstfruits from those who have fallen asleep” (Νυνὶ δὲ Χριστὸς ἐγήγερται ἐκ νεκρῶν, ἀπαρχὴ τῶν κεκοιμημένων). You can’t really have a resurrection without real, true death. Without laying your body down in the midst of history’s pile of corpses.

Resuscitation, maybe, you could find. Certainly there are plenty of those every year, natural and occasionally supernatural if the medical term “spontaneous regeneration” gives any clues alongside the eye witness accounts of various peers whom I trust within various international contexts. There are also those mythologies of folks having sex with corpses and siring children, which is a kind of life after death. Or the gnostic (or often nihilistic) idea of the soul in the “sweet by and by” life after death. I once heard a preacher say that we lose our personalities after death in a blinding vision of God — whatever that is, it’s not resurrection and it most certainly is nihilistic to the same degree Prime Day renders everything meaningless. Or Achilles who said that the mere existence of the story of the Iliad would ensure his immortality as his name would live forever, Achilles who never directly braved the underworld the way Orpheus did. There were gobs of ideas about the afterlife prior to the first century.

But life after “life after death” ? A true life 2.0 with a new body brought beyond the very threat of death, the kind of thing that rewrites the very code of entropy within the fabric of the universe, as the Cambridge chair of physics John Polkinghorne might have said? That was black swan kind of idea, one that could not have been conceived prior to the first century.

Resurrection as a kind of price cannot be held. It’s simply the cost — to defeat death with resurrection, the risen one must die real, lasting, three-days-doornail-dead death. No “I’m not dead yet.” No revision, no resuscitation, no mere seasonal corn god brought back every spring. Stone cold dead, no take backsies.

Interestingly enough, Greggory of Nyssa believed that someone did receive that price. Nyssa thought Satan received the manumission fee of the corpse of the Author of Life. Satan? Who is that? He’s that disembodied super intelligence even Elon and Bill Gates fear when they say Ai is “summoning the demon”; the great malign intellect; the corrupted infinite idea of killing things for one’s pride and power; the principality of entropy himself. According to Nyssa, the ruler of this dying world held onto that price of resurrection within the realm of hell, of Hades, of death. By holding on to the price of resurrection, the demon of our culture of death would — after many, many eons — himself change: fishhook of the Godhead set in his lips, he could do nothing but give up Hades and his pride and himself rise anew.

Healed.

At that moment, death per se would die. Entropy would suffer entropy. Decay would rot. Hades would be thrown into the lake of fire.

In the first and last cry of that cosmic nativity, that New Heavens and New Earth, a paradise would be built right in the middle of hell. The angels having braved the flames to bring the price of resurrection to the fallen angels, even the fallen angels would find themselves rescued.

Whether you believe that or not — most of you are not Christian in any way shape or form and many of the Christians reading this favor the sadomasochistic version, while still others who do not like mythology will wonder why we haven’t touched on historical record assembled by that one Oxford don12 — I still have an extremely specific point.

You ready?

Though that long walk through ancient mythology may or may not yet appeal to you, consider it all in the light of the rest of Los Angeles’s flickering flames — all of Solnit’s and my own experiences with disasters. Consider it all when you face your own response to your neighbor:

At times like these, the mere possibility of the mythology of resurrection being made manifest just once in history teaches us to cast off our petty optimisms. To toss away mere incremental improvements, mere perfected societies, mere talks of how we can invent our way out of a problem we started with our own inventions. We do live in a world of death. We do. Entropy is a thing. At least for now. Fires do take everything from us right now — as do floods and storms and the rest and post-disaster scammers come and exploit the homeless or loot their homes, adding insult to injury.

And yet the very existence of our consciousness — our understanding of history — begs the question: why do we grieve at all?

Because death is a lie. It hurts because every time, every single time, these damn disasters feel absolutely unreal, other worldly, like something out of some nightmare from which we all very reasonably hope to one day waken. Tolkien would have said this is precisely why we write escapism: to give ourselves an escape plan from this prison. To give ourselves a reason and a plan to fight it.

In these moments, the story of resurrection tells us not to have optimism. No. The story teaches us to hope instead. In these moments it takes an incredible amount of conviction to hold onto what reason once accepted as true, despite our changing moods. It takes an incredible amount of what Rothfuss called “riding crop” faith — assurance in what’s hoped for, belief that Being is stronger than nonbeing, belief that resurrection will ultimately rewrite the rules of entropy, as Dr. Polkinghorne — Cambridge’s former chair of physics — once claimed.

Belief that devastating wildfire itself will be thrown into the lake of fire.

That one day the little girl suffering from skin burns in the dark haze of wildfire smoke will be lifted up, every tear wiped from her eye, every meaningless scar healed including the scar tissue on her lungs, every burn salved, and there will be no more tears for her or her family or anyone else.

In that day, we all shall build our gilded homes upon these streets of ash.

Why bring up these myths?

Well for one, practicing resurrection at very least means that if you believe you’re the sort of person who has never met a mere mortal — if you believe that you will have physical life again and that entropy will be unmade — you have no reason to, for instance, need a firearm for self-protection. There is no greater self defense than the resurrection of the self. None. If you, yourself, will experience corporeal life again, why fear death? So “you loot, we shoot” looses its steam, especially from anyone who every confessed, “I believe in the resurrection.”

You stop fearing your neighbor in any real or ultimate sense immediately. You quit your addiction to xenophobia, racism, and hatred of the person you do not know or have not met. You start to love the stranger, the foreigner.

But that’s merely the negative example. There’s another reason, a positive momentum:

See this kind of riding crop faith helps us pick up a hose and help our neighbor fight the coming flames. The Great Day of Service helped Joplin once. It took conviction, it took community collaboration, and it took the systematic virtue ethics of eight years practicing serving our fellow neighbors. Again, it wasn’t just Catholics or just evangelicals — it was the Mormons, the synagogue, the mosque, everyone. But that city-wide practice won out to help us all go all-in when the chips were way down.

Such a Day could help again.

In the comments, consider committing with your friends to starting an annual Great Day of Service in your town or city.

Will you love your awkward, strange, even downright hostile neighbor? Be it your next door neighbor, your next neighborhood over neighbor? Your neighbor on the other side of the tracks, the street, the mountain? Your red state neighbor or blue state neighbor? Your poor or rich neighbor? Your sick or healthy neighbor? Your believing or unbelieving neighbor? Your heretical or orthodox neighbor? Your powerful or shamed neighbor? Your arrogant or self-loathing neighbor? Your global neighbor? Your racially, sexually, ideologically other neighbor?

Who is your enemy?

Would you help clean their house or come to visit their town and share a meal? If they reached out to you for mediation counseling, would you accept the offer?

Would you — and I know many reading this have literally said this in bitterness or resentment — put them out if they were on fire?

What would happen if you became the kind of person who forgave them anyway and did put them out if they were on fire?

What would society look like tomorrow morning?

How beautiful would it be?

There once was a man who not only served bread and wine, but who stripped down to his underwear to scrape donkey shit from out between the callused toes, who washing the feet, of his best friend who would later that night sell him out for thirty shekels in some desperate attempt to force him to revolt violently. The betrayer was a “you loot, we shoot” kind of guy. That act of blackmail failed.

That same night, the foot washer disarmed his other best friend of his sword. He said, “Love your enemies.” He’s the same guy who, as the story goes, harrowed hell to release the captives held there, snuffing out the torture of those eternal flames forever.

Will you practice resurrection? Will you be an angel who braves hell? It’s right there in the name: Los Angeles Fires. There were no longer three men in the fire.

There were four. And they will not harmed.

Will you start a Great Day of Service?

Decide quickly, please, because our world is currently burning to the ground and we could use some help over here…

Astonished, King Nebuchadnezzar stood up in terror, and asked his advisors, “Didn’t we throw three men into the fire, bound firmly with ropes?”

In reply they told the king, “Yes, your majesty.”

“Look!” he told them, “I see four men walking untied and unharmed in the middle of the fire, and the appearance of the fourth resembles a divine being.”

Then Nebuchadnezzar approached the opening of the blazing fire furnace. He shouted out, “Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, servants of the Most High God, come out and come here!” So Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego came out of the fire.

— Daniel 3:24-26

Response and Recovery after the Joplin Tornado: Lessons Applied and Lessons Learned By Daniel J. Smith, Daniel S. Sutter. “Voluntary-sector efforts have been an enormous part of the response-and-recovery efforts in Joplin. As of November 2011, more than 92,000 registered volunteers—including 749 different church, charity, business, hospital, and school groups—had contributed more than 528,000 person-hours to the recovery process. Volunteers came from nearly every state in the United States and from as far away as Japan and removed 1.5 million cubic yards of debris, about half of the storm’s total. Individuals, churches, and community organizations supplied thousands of meals to first responders immediately after the tornado and to the volunteers who arrived later during the rebuilding phase. The response from the voluntary sector in the immediate tornado aftermath revolved around church and business groups. As one Joplin business owner observed, “I don’t think we can say enough about the volunteers. Whether they be local people [or not]. . . . We know people who had no damage; maybe their business was closed because they had no power, the factory they worked was closed, and they went out and got a chainsaw and their pick-up, went out to some street or a friend’s house or a neighbor’s house, and started clearing and cleaning, and this part of Missouri is pretty self-sufficient. . . . Somebody joked about how everyone in Joplin must have a chainsaw.”

The Response to the 2011 Joplin, Missouri, Tornado Lessons Learned Study. FEMA. Points of contact (POCs): Chuck Gregg, Lisa Lofton.

Sun, 09.21.1947 — St. Louis Parochial Schools Integrate, African American Registry.

Culture Care, Makoto Fujimura.

Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit, 2.

Solnit, 4-5.

Solnit, 14.

Solnit, 17-18.

The Resurrection of the Son of God, N.T. Wright.